There is an unsettling shiver on the air, a darkness on the waters where the light should fall… yes, it’s Folk Horror Time once more, and today we have a mover in the movement, that gifted artist (and occasional writer) Cobweb Mehers with us to talk about everything from Goth music to sculpture and the art of the Upper Palaeolithic. We make it sound as if we know what we’re talking about, and Cobweb makes it clear that he does. It’s our big interview for this week, so we’ll get straight down to it…

greydog: Welcome to greydogtales, Cobweb. Many of your areas of interest seem to overlap with ours, so we may be testing you today, quite unfairly. We first came into contact via the Folk Horror Revival movement. Did you yourself get involved with the Revival from a folklore background, a love of horror, or both?

cobweb: Initially I got involved to support a friend. Andy Paciorek (see interview with the weirdfinder general) had some very big ideas and his enthusiasm and vision was a little contagious. It was a genre I was only vaguely aware of by name but I was already very at home in that aesthetic. I enjoy a lot of the related music and films but my real interest lies more with folklore inspired art. It was through Andy’s Strange Lands book that I started to get to know him, so that was my starting point.

I’m very excited about the various projects the group is looking at for the future. There is an enormous wealth of musical, artistic, and literary talent within the group and it’s great to see people interacting and bouncing ideas around. There’s so much more going on in the background that you don’t really see on the Facebook group. It really is the start of a revival and evolution of Folk Horror and I expect to see great things come from it.

greydog: We agree with that, and are enjoying the Revival immensely. You may have noticed that despite the lure of dark forests and sacred groves, we draw a lot of inspiration from the sea and its boundary with the land. Do you have any affinity for the cold grey waters, or are you a woodsman when you seek out folk influences?

cobweb: I’m very much a sacred groves kind of person. I lean far more towards Machen’s Pan than Lovecraft’s Deep Ones, but I do have a thing for liminal zones. When I lived on the North East coast my favourite thing was to walk deserted beaches in thick fog. You’re caught between the sea and the land but both are silent and indistinct.

greydog: It’s a perfect moment. Now, you’ve spoken elsewhere of your admiration for the group The Fields of the Nephilim. As we don’t really cover enough music here (and we love their album Dawnrazor), maybe you could say a bit about this for our listeners?

cobweb: Dawnrazor was a revelation to me. I was 15 when I first heard it and it completely changed the way I saw the world. Initially it was more a case of atmosphere and style but the substance came with time. They’re a band I’ve grown up with and they’ve grown with me. I’m still finding new ideas and inspiration in their work. Fields of the Nephilim have been a catalyst for most of what I’ve done in one way or another.

When I first discovered the internet in the late 90’s I spent many happy hours dissecting their lyrics with other fans and discussing the inspiration behind songs. I established friendships with people across the world who shared my interests in the esoteric, ancient history, archaeology, and myth. Most of them I’ve since met in the flesh and count amongst my closest friends.

It was through his work on the first Fields of the Nephilim videos that I got to know Richard Stanley. While we no longer see eye to eye, it was Richard who first invited me to visit Montsegur and experience the high strangeness of the Languedoc up close and extremely personally. It’s an amazing part of the world; initially I was drawn to it as during the Middle Ages it was a melting pot of esoteric and heretical ideas from across Europe and the Middle East, but there have been people there for over thirty thousand years so there’s a lot more to it.

In the Upper Palaeolithic it was where all the coolest artists and magicians hung out and it has been ever since. I fell in love with the region and go back whenever I can to climb the mountains of the gods, visit the sacred groves, and explore lost ruins and secret caves.

greydog: Speaking of the offspring of fallen angels (cheap link), we were always disappointed that the Book of Enoch was considered non-canonical – Azazel and the Watchers etc. And then we saw your piece about the Biblical Nephilim in the Folk Horror Revival book ‘Field Studies’. What interests you about this particular theme?

cobweb: It’s a subject I’ve been obsessed with for decades. It actually predates my love of Fields of the Nephilim and is what initially made me listen to the band. The reason it interests me has changed dramatically over the years as I’ve discovered more about it. The mythology grew out of a pivotal moment in the history of civilisation. On one level it’s our way of coping with the leap from nomadic hunter-gatherers to settled agriculturalists.

There are definite historical events that lie behind it that are probably nowhere near as exotic as the stories, but there’s also a spiritual aspect to what happened that’s much harder to pin down and unsettlingly pervasive. What may come down to little more than an argument about sharing technology and a fear of climate change thousands of years ago still forms the basis of the way we perceive the world. We can’t forget even if we can’t quite remember what it is we can’t forget. It’s something I find endlessly fascinating.

greydog: Let’s talk about your artistic work. You’re the talent behind Eolith, which specialises in a range of striking mythic and pre-history sculptures. Is the work you do for Eolith your main day-to-day focus, or just one of many sidelines?

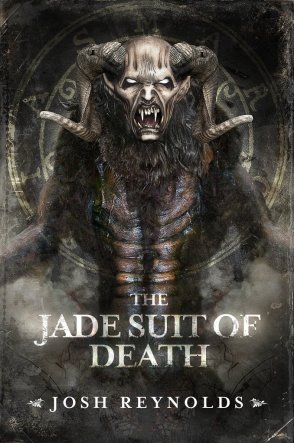

cobweb: Eolith Designs is the platform for any work that’s my own idea rather than for commissions. I try to make it my main focus but I get distracted by other projects from time to time. I’ve just finished a cover design for Volume 6 of Cumbrian Cthulhu (cumbrian cthulhu), which I think comes out in the Autumn, and I’ll be doing some illustrations for upcoming Folk Horror Revival fiction releases.

greydog: We believe that you contributed to the British Museum’s exhibition “Ice Age art: arrival of the modern mind” a few years ago, is that right?

cobweb: Initially the British Museum wanted to sell some of my Ice Age art inspired sculptures in conjunction with the exhibition. I also offered to create a new work based on one of the pieces in the exhibition. It’s a thirteen thousand year old carving called The Swimming Reindeer and it means a lot to me personally but I’d not accounted for anyone else being as interested in it as I was. I expected to sell a dozen at most but it was insanely popular. I spent nearly a year doing little more than making reindeer and three years after the end of the exhibition they’re still selling them.

greydog: Which do you prefer, the detailed recreation of a genuine early artefact or having licence to experiment with mythological imagery?

cobweb: The Swimming Reindeer is the only sculpture I’ve done where I deliberately set out to do a detailed recreation. The British Museum sent me loads of very nice photographs and that forced me to work in a completely different way than I usually do. Even that isn’t an exact reproduction, but having seen mine in the same room as the original it isn’t far off.

The work I’ve done based on genuine artefacts has generally been a result of me trying to get inside the head of the original artists and work out why they did things the way they did. Everything is an experiment and an exploration of ideas. I do a lot of research before I start anything and I sculpt quite slowly so the process forces me to spend a long time focused on thinking about one particular thing and that is gradually distilled into the final piece.

greydog: You also do ‘flat’ art, of course. Do you find it less satisfying than sculpture?

cobweb: I probably paint and draw more than I sculpt, but I approach 2D art in an entirely different way. I use it for more immediate things; recording dreams and visions and things glimpsed at the more exotic ends of the consciousness spectrum. It’s not the kind of thing that lends itself well to going on people’s living room wall. I’ve been pondering putting a book together for a while now, as I think that would probably be a better format for them, but it’s finding the time.

greydog: We read once that you have an interest in Ugaritic studies, which would seem terribly niche except that we do too. In our case, it’s because of the Dagon/Ioannes connections and the whole Hittite and Sumerian mythology scene. This is an amazing resource for the stranger branches of fiction, including the Cthulhu Mythos writers – and bits of our own work. How did you get into the subject?

cobweb: This was another side effect of my Nephilim obsession. The Nephilim turn up in Canaanite myth as The Healers and they feature in the literature found at Ugarit. I very quickly developed a fondness for Canaanite culture and mythology. There’s a deceptive simplicity to it and a humanity that’s very easy to relate to even today. I have a particular affection for the goddess Anat; there’s a touch of genius to personifying war as a teenage girl. The Devourers are also worth looking into. They’d be right at home in a Lovecraft story.

greydog: As you know, weird fiction is at the heart of greydogtales. We’re guessing that you’re quite well-versed in that area – which writers resonate with you?

cobweb: I don’t read a lot of fiction these days but when I do it tends to be the classics of that particular genre. I discovered Lovecraft first and again that was down to Fields of the Nephilim. We’ve become overly familiar with him in many ways and he’s not taken seriously enough. He’s not the greatest writer from a technical point of view but there are still things in his work that are actually really scary even after repeated rereads.

Machen I identify much more with and I enjoy his non-fiction as well as his stories. I’d love to have met him partly because I have a lot of questions, but mostly because I think we’d have got on really well. I’m also quite keen on Lord Dunsany and have been known to dabble with Clark Ashton Smith.

greydog: And to finish with, our perennial question – what’s coming from you in the next year? Any plans or projects you’d like to share with us?

cobweb: I have a couple of new sculptures in progress that should see the light of day before too long. One is my interpretation of what archaeologists call Judean pillar figurines, because archaeologists have no imaginations. The other one will eventually be one of a pair and is an exploration of ideas about the Nephilim covering a lot of history and geography. His other half will have to wait for a while though because the big project for the rest of this year will be jewelry.

I started my artistic career making jewelry and it was always something I intended to come back to when I started Eolith Designs. I’m really just aiming to make tiny wearable sculptures in silver.

greydog: Thank you very much, Cobweb Mehers, it’s been a pleasure talking to you. If you’d like to see, or know more about, Cobweb’s sculpture and design work, have a look here:

Not forgetting the music – if you don’t know the Neph then you can listen to the Dawnrazor track itself here:

And why not try exploring the Folk Horror Revival. We think it’s great. The website’s below, and the first book’s on the sidebar.

Next time: Don’t ask. Just don’t ask. Our brains hurt, and the dogs need to go out…