By some strange accident, we recently went mountaineering. No, not really. But we did happen to re-read a range (thank you) of hillish stories in the space of a fortnight or so, mountains of madness all. So we vaguely thought about covering stories by E F Benson, H Russell Wakefield, H P Lovecraft, Manly Wade Wellman and Jerome K Jerome all at once. Then we received PR about a new book from Crystal Lake Publishing, and saw the words ‘Bavarian Alps’. It was meant to be.

We haven’t read The Third Twin by Darren Speegle, but we will tell you what we know about it later below. On the other hand, we have read the following five stories many times. They range from the classic supernatural to folk horror, with solid Mythosian cosmic horror in there as well.

Quite what a mountain means in weird and supernatural terms is very variable. In folk horror terms, it conjures up isolated communities, lonesome souls, and maybe relics of earlier beliefs. The psychogeography of mountain horror is a mix of small huddled places and vast, almost incomprehensible heights. In purely natural terms, communications are poor or almost non-existent; the weather is treacherous, and the risks of being lost and dying without ever being found are many.

The mountain is rarely seen as a nurturing thing, and often considered to be actively hostile. It’s also seen as symbolic of age, of permanence and of unimaginable scale.

“The Thing cannot be described—there is no language for such abysms of shrieking and immemorial lunacy, such eldritch contradictions of all matter, force, and cosmic order. A mountain walked or stumbled.”

Call of Cthulhu, H P Lovecraft

Things survive in the mountains which should not – supernatural beings, forgotten branches of humanity, dying pre-human cultures and the like. The mountains are often a last refuge. But, hey, this is not an essay, so here are our five mountains of madness in chronological order, with the occasional trivia and diversions added…

Mountains of Madness 1: The Woman of the Saeter

by Jerome K Jerome

We said quite a bit about Jerome K Jerome last week. This story, published in John Ingerfield: And Other Stories (1894), is one of his few dark supernatural stories, and is set in the mountains of Norway:

“For hour after hour you toil over the steep, stony ground, or wind through the pines, speaking in whispers, lest your voice reach the quick ears of your prey, that keeps its head ever pressed against the wind. Here and there, in the hollows of the hills lie wide fields of snow, over which you pick your steps thoughtfully, listening to the smothered thunder of the torrent, tunnelling its way beneath your feet, and wondering whether the frozen arch above it be at all points as firm as is desirable. Now and again, as in single file you walk cautiously along some jagged ridge, you catch glimpses of the green world, three thousand feet below…”

It’s a tale of twisted love, with a surprisingly powerful evocation of relationships which turn to hate, and of ghostly vengeance, set against the backdrop of the saeter. What’s that, you ask? A saeter is both a Scandinavian mountainside meadow used seasonally for grazing milking cows or goats, and a cabin found in such a meadow.

“Giving one swift glance about him, our guide uttered a cry, and rushed out into the night. We followed to the door, and called after him, but only a voice came to us out of the blackness, and the only words that we could catch, shrieked back in terror, were: “Sætervronen! Sætervronen!” (“The woman of the sæter”).”

Scary and satifying. You can read this on-line here: https://americanliterature.com/author/jerome-k-jerome/short-story/the-woman-of-the-ster

Mountains of Madness 2: The Horror Horn

by E F Benson

‘The Horror Horn’ was published in 1922, in Hutchinson’s Magazine, and is set in the Engadine, which is a long, high Alpine valley region in the eastern Swiss Alps.

This is a tale of mountaineers and monsters, drawing on the idea of the lost branches of humanity and linked to concepts such as Neanderthal survivals, Big Foot, Yeti and so on.

“’Not twenty yards in front of me lay one of the beings of which he had spoken. There it sprawled naked and basking on its back with face turned up to the sun, which its narrow eyes regarded unwinking. In form it was completely human, but the growth of hair that covered limbs and trunk alike almost completely hid the sun-tanned skin beneath. But its face, save for the down on its cheeks and chin, was hairless, and I looked on a countenance the sensual and malevolent bestiality of which froze me with horror. Had the creature been an animal, one would have felt scarcely a shudder at the gross animalism of it; the horror lay in the fact that it was a man.’”

It also brushes the psychogeography of mountains, the curious effects that they have on the mind:

“But the fact that night would soon be on me made it needful to bar my mind against that despair of loneliness which so eats out the heart of a man who is lost in woods or on mountain-side, that, though still there is plenty of vigour in his limbs, his nervous force is sapped, and he can do no more than lie down and abandon himself to whatever fate may await him…”

It’s not our favourite Benson story, but it is a popular one. The full story can be read or downloaded here https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/b/benson/ef/horror-horn/

Mountains of Madness 3: At the Mountains of Madness

by H P Lovecraft

Written in 1931, this long story was serialized in the February, March, and April 1936 issues of Astounding Stories. This time we are at the other end of the world, in Antarctica, though the title comes from a piece by Lord Dunsany, ‘The Hashish Man’ (1910).

“Then the two spirits rushed at me, and swept me thence as gusts of wind sweep butterflies, and away we went from that small, pale, heinous man. There was no escaping from these spirits’ fierce insistence. The energy in my minute lump of the drug was overwhelmed by the huge spoonsful that these men had eaten with both hands. I was whirled over Arvle Woondery, and brought to the lands of Snith, and swept on still until I came to Kragua, and beyond this to those bleak lands that are nearly unknown to fancy.

“And we came at last to those ivory hills that are named the Mountains of Madness, and I tried to struggle against the spirits of that frightful Emperor’s men, for I heard on the other side of the ivory hills the pittering of those beasts that prey on the mad, as they prowled up and down.”

Plenty has been said elsewhere about ‘At The Mountains of Madness’, so we won’t bang on about it. It includes a magnificent vision of the mountains of Antarctica, with HPL’s added cosmic horror touch:

“The sailor Larsen was first to spy the jagged line of witch-like cones and pinnacles ahead, and his shouts sent everyone to the windows of the great cabined plane. Despite our speed, they were very slow in gaining prominence; hence we knew that they must be infinitely far off, and visible only because of their abnormal height. Little by little, however, they rose grimly into the western sky; allowing us to distinguish various bare, bleak, blackish summits, and to catch the curious sense of phantasy which they inspired as seen in the reddish antarctic light against the provocative background of iridescent ice-dust clouds.

“In the whole spectacle there was a persistent, pervasive hint of stupendous secrecy and potential revelation; as if these stark, nightmare spires marked the pylons of a frightful gateway into forbidden spheres of dream, and complex gulfs of remote time, space, and ultra-dimensionality. I could not help feeling that they were evil things—mountains of madness whose farther slopes looked out over some accursed ultimate abyss.”

Having first read this in our early teens, it has stayed with us so firmly that we won’t bother to critique it. We know that some people feel it needed editing down and making more coherent as an overall work. One aspect that still interests us is an unusual element for Lovecraft. He writes with a surprising sense of empathy at key points for the Elder Things, who have had to face their own ancient terrors, and have now been woken from aeons-long slumber to yet another threat.

Otherwise, it’s a definitive piece for aspects of what later became known as the Cthulhu Mythos. Easily found in full on-line.

Mountains of Madness 4: The Third Shadow

by H Russell Wakefield

“The Third Shadow” was the cover story in the November 1950 Weird Tales, being written late in H Russell Wakefield’s career. We don’t always get on with him, we confess. He wrote some very decent scary stories, but he gets a bit misogynistic now and then – or seems to. H P Lovecraft’s view was that Wakefield “manages now and then to hit great heights of horror despite a vitiating air of sophistication”, which is not far off.

Here we have a true ‘high peaks’ mountaineering story, with all the detail of routes and equipment you might want. As with ‘The Woman of the Saeter’, it has at its core the theme of relationships, and this one has the same dark touch of vengeance. It takes the form of a reminiscence of a tragedy, and of the strange things that may occur under the pressure of climbing.

It also includes some nice observations for our ‘mountains of madness’ concept:

“I grant you, also, I myself have sometimes felt that over, say twelve thousand feet, one moves into a realm, where nothing is quite the same, or, perhaps, and more likely, it is just one’s mind that changes and becomes more susceptible and exposed to—well, certain oddities.”

“Certain pious, but, in my view, misguided persons, profess to find in the presence, the atmosphere, of these doomed Titans, evidence for a benevolent Providence, and a beneficent cosmic principle. I am not enrolled in their ranks. At best these eminences seem aloof and neutral, at worst, viciously and virulently hostile—I reverse the pathetic fallacy. That is, to a spirited man, half their appeal. Only once in a long while have I been lulled into a sense of their good-will.”

Not a bad tale. You can read it on-line here: http://www.unz.org/Pub/WeirdTales-1950nov-00024

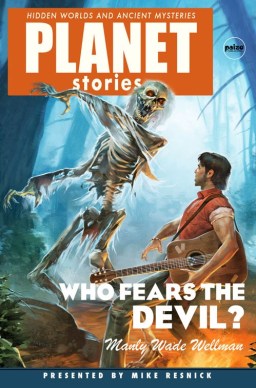

Mountains of Madness 5: The Desrick on Yandro

by Manly Wade Wellman

As Wellman’s excellent John the Balladeer stories are set in the Appalachian mountains, it was hard to pick only one entry. This might have easily been ‘Walk Like a Mountain’, which blends folk-lore with an Enochian inheritance.

“He sat down on a rock, near about as tall sitting as I was standing. ‘Ary giant knows he was born from the sons of gods,’ he said. ‘My name tells it, John.’

“I nodded, figuring it. ‘Rafe – Raphah, the giant whose son was Goliath, Enoch -‘”

But ‘The Desrick on Yandro’, from the 1952 issue of F&SF, remains one of Wellman’s classic tales. Lost love – or twisted love, and a huge sense of the Appalachian trails and ways. We’ve almost come full circle here, back to the mountainside saeter – a desrick is roughly built cabin or shanty, originally from Appalachian and North Carolinian dialect.

‘That’s the Yandro Mountain,’ she said. ‘There, on the highest point, where it looks like the crown of hat, thick with trees all the way up, stands the desrick built by Polly Wiltse. You look close, with the sun rising, and you can maybe make it out.’

And we mentioned survivals in the mountains earlier. Yandro is plumb full of those, strange beasts which few have ever seen.

“’Oh, there’s other creatures, too. Scarce animals, like the Toller.’

“’The Toller?’ he said.

“’It’s the hugest flying thing there is, I guess,’ said Miss Tully. ‘It’s voice tolls like a bell, to tell other creatures their feed’s near. And there’s the Flat. It lies level with the ground, and not much higher. It can wrap you like a blanket.’ She lighted the pipe. ‘And the Bammat. Big, the Bammat is.’”

Yandro is an odd word, and supposedly taken from an old folk song which came originally from Britain, mutating as so many did in the mountains of madness. The song has many names, including He’s Gone Away, Yandro, and Over Yonder:

He’s Gone Away

I’ll go build me a desrick on Yandro’s high hill,

Where the wild beasts won’t bother me nor hear my sad cry

For he’s gone, he’s gone away for to stay a little while,

But he’s comin’ back if he goes ten thousand miles.

‘The Desrick on Yandro’ has a wonderful feel, an ending that satisfies, and is still highly recommended.

The Third Twin

To finish with, we remember the Bavarian Alps trigger that started this off, and give you the blurb for The Third Twin by Darren Speegle, which came out on 28th April this year from Crystal Lake Publishing. If we manage to get a copy at some point, we may even tell you what we think later in the year.

“Barry Ocason, extreme sportsman and outdoor travel writer, receives a magazine in his mailbox and opens to an ad for an adventure in the Bavarian Alps. Initially dismissing the invitation, which seems to have been meant specifically for him, he soon finds himself involved in a larger plot and seeking answers to why an individual known only as the elephant man is terrorizing his family.

“Barry and his daughter Kristen, who survived a twin sister taken from the family at a young age, travel from Juneau, Alaska to the sinister Spider Festival in Rio Tago, Brazil, before he ultimately answers the call to Bavaria, where the puzzle begins to come together.

“Amid tribulation, death, madness, and institutionalization, a document emerges describing a scientist’s bloody bid to breed a theoretical “third twin,” which is believed to have the potential, through its connection with its siblings, to bridge the gulf between life and afterlife. The godlike creature that soon emerges turns out to be Barry’s own offspring, and she has dark plans for the world of her conception that neither her father nor any other mortal can stop.”

The Third Twin is available here: http://getbook.at/ThirdTwin and you can check out Crystal Lake‘s other stuff at their website www.crystallakepub.com