The final free story of our winter tales from JLG this year is a bit different — a winter solstice on its way, a piece of quiet folk horror set in Northern England in 1975…

“Our first mistake was the car we hired in York. I rarely drove; Petersen was used to London and the flatlands. It soon became obvious that we would have been better hiring a Landrover than the large, comfortable Ford Granada we had been offered. This was late November, and although we’d avoided snow as yet, every route to Kemberdale involved narrow lanes lined with drystone walls, sudden lurches into precipitous inclines, and poorly-metalled country roads. Crossing the purple and dark green expanse of the moors proper, Petersen jerked the wheel at every idle sheep in the road and every bird which broke from cover.”

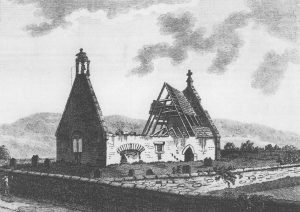

This was first published in Lonely Hollows, Pavane Press 2023, and as it happens, this rather neat cover was inspired by my contribution.

If you would simply like a free download to read later on some abnatural mechanical device, click the link right below:

kember-jlgscreen

THE BEASTS OF KEMBERDALE

by John Linwood Grant

North Yorkshire, 1975

I shall call the place Kemberdale, in order to spare those who deserve their anonymity. It is real, though—one of those small communities on the edge of the bleak North York Moors. Perhaps once it straddled a Roman road, or a later pack-trail between more important destinations, but now it stands disconnected, isolated. Farming land, with little to commend it to outsiders—none of the ruined buildings or interesting vistas which delight ramblers and amateur photographers. Sheep on the hillsides; wheat and potatoes in the fields.

Archie Crane mentioned it to me, at a dull party in Chelsea. Archie is a touch pestiferous, and will poke his nose into others’ affairs.

“Young Petersen has his eye on a collection held by the local lord of the manor. I say ‘lord’, but he’s just a jumped-up farmer, really.” Archie refreshed our glasses. “Anyway, they say there are a few oddities up there, and Petersen thinks they’re worth a look…”

The conversation swung to gossip about a sculptor we both knew, and I thought nothing of it until I bumped into Erik Petersen later that week at a wine-bar.

“Fancy an adventure, Justin?” Petersen was a tall blond, a fine echo of his Scandinavian forebears. “I need to go north later this week.”

“Kemberdale?”

His eyes widened, then narrowed with suspicion. It spoiled his good looks.

“Are we in competition?”

I laughed. “I don’t even know what’s up there, and no-one’s asked me to go hunting, if that’s what you mean. I’m carefree—and commission-free—at the moment.

He relaxed. “Oh, well, I know you’re fond of Yorkshire, and you do have an eye for curios, so I wonder…”

“What’s the quarry?”

He stubbed out his cigarette and leaned closer.

“I have it on good authority that there used to be a number of quaint practices in the area, the sort of thing that people keep trying to revive.”

“Dear God, not druids?” An unfortunate encounter the previous year, involving suburban accountants, had quite put me off that area. Little was worse than middle-class Englishmen—or women—donning robes and wandering round spouting pseudo-Celtic nonsense without the faintest idea of what they were doing.

“No, genuine folk history. Chap up there wrote to say that he has some costumes; mumming, sword dances—that sort of game—including a nice set of masks.”

It wasn’t particularly my field, but I’d submitted my column to ‘The Sculptor’ magazine, knocked off a couple of articles for The Times, and completed a large estate valuation, so a trip up North might provide a pleasant break. Petersen was easy on the eye, and decent company.

“I could be free by Thursday,” I offered.

We agreed the details there and then.

*****

Our first mistake was the car we hired in York. I rarely drove; Petersen was used to London and the flatlands. It soon became obvious that we would have been better hiring a Landrover than the large, comfortable Ford Granada we had been offered. This was late November, and although we’d avoided snow as yet, every route to Kemberdale involved narrow lanes lined with drystone walls, sudden lurches into precipitous inclines, and poorly-metalled country roads. Crossing the purple and dark green expanse of the moors proper, Petersen jerked the wheel at every idle sheep in the road and every bird which broke from cover.

“Christ, what was that?” he said as he almost took us into a ditch.

“Pheasant. For goodness sake, Erik—are you expecting spear-wielding natives to burst out of the bracken?”

In time, and after a few accidental detours, we spotted a lichen-covered wooden post with a sign which could just be made out: Kember 5 miles. The rest of the journey was a low-gear crawl down into a valley bottom, and on through a scatter of stone cottages to our destination.

Kember Manor was the only building of note in sight—a farmhouse fortified in the manner more commonly found on the Scottish borders. No doubt the northern dales had seen their share of sheep and cattle rustling.

I wouldn’t have called the manor attractive—the thick walls appeared a mix of gritstone and brick, unevenly plastered, with lank ivy hiding a good third of the two storey building, which could have been 16th or even15th century. A few small, quartered windows were scattered across the frontage as if afterthoughts, looking out over a pitted gravel drive which meandered between barns and chicken-huts.

“Chap we’re going to see is a Samuel Beckshaw. His family have lived around here since Adam; he owns most of the houses hereabouts. Has the only telephone in Kemberdale, would you believe?”

“That’s one more phone than I might have expected,” I said, conscious that the landscape was fading into a charmless dusk. “Are we going to drive back to York in the dark?”

“No, Beckshaw’s putting us up for the night—he wanted me to come as soon as possible.”

I hadn’t been able to get a straight answer as to whether Petersen was buying any of this stuff, or simply viewing it and looking to catalogue it, but I’d been promised a couple of nights in a decent York hotel when we’d finished in Kemberdale.

Petersen slid the Granada to a halt in a patch of mud by the nearest barn, and pronounced himself content.

“Four o’clock. Not bad time, really.”

I said nothing. We were supposed to have been here by two in the afternoon.

A cold wind cut across the manor yard, bringing with it the smell of rank vegetation and stagnant water; it smelled as if the entire area could do with a good hosing down, and perhaps a few barrels of carbolic. But the door was answered promptly by a man at odds with these surroundings—a well-dressed man in his late twenties, clean-shaven, red-cheeked and redolent of Old Spice.

“Mr Petersen—you made it.” He looked relieved to see us. “And this would be…”

“Justin Margrave,” I said, extending a hand. His grip was firm, too firm.

“Good, good. Do come in.”

He showed us into a large, barely furnished room with whitewashed walls.

“Where the cattle would have sheltered during raids,” I murmured, and Beckshaw smiled.

“Quite right. With a few modifications.” He indicated a pair of ancient leather sofas, and a set of closed pine cabinets which lined the long far wall.

“By your accent, you’re not from Yorkshire, Mr Beckshaw?” I ease myself into one of the sofas, expecting mice to shoot out of its seams.

“Born here—in this house—but I was abroad for years. In France. Came back when my father died this summer. Cancer.”

“My condolences.”

“Yes.”

Not ‘Thank you’, but ‘Yes’. His smile had gone, and I changed the subject.

“So, Petersen tells me you have some fascinating pieces. I’m more in the sculpture line, with a touch of ceramics and bric-a-brac, but still, I imagine–”

“Time presses, Mr Margrave.” Beckshaw’s interruption was accompanied by the jangle of keys, drawn from his jacket pocket. “I know you’ll think me rude, but I’m hoping to rid myself of this lot as soon as possible…”

“Of course.”I was used to odd customers, and Petersen had an acquisitive gleam in his eye.

“Let me show you what I have. We can have a drink later, and maybe come to terms.”

He unlocked the row of cabinets, five in all. The were tall, not that old, but the contents clearly went back many years, and I found myself stepping closer…

The display before me was reminiscent of a theatrical costumiers I had visited, not long after the war, a warren of a place packed with the most gorgeous and most tawdry racks of gowns and robes, fake jewelled necklaces; sceptres, hats and masks. This looked like its rural, folk museum equivalent.

“Feel free to browse, assure yourself that it’s all genuine.”

We did, and we did.

Thick woollen robes, dyed green and crimson, smelled of another time; furs were moth-eaten in that way which only many decades could achieve. Petersen lifted out a horse skull, gaily coloured but faded, which must have been from a mummer’s hobby horse.

“Early Victorian, at least,” he said, showing it to me. “Brass fixings for the pole, heavily used.”

In the cabinet nearest me were blades typical of the traditional sword dances of the North—rigid steel with simple wooden hilts, the varnish peeling—and padded black ceremonial jackets. The casual heap of jackets was topped by a basket of belled anklets, typical of Morris dances and similar going-on. And there was much more along the same lines.

“Is all this from around here?”

“I don’t know—I didn’t collect this junk. I tried to get rid of it all last month, but none of the museums I rang had enough space or interest to come through in time.”

“In time?”

“You’ll understand in a minute. Here…”

Beckshaw stood back from the last cabinet, holding the door wide open.

This one was shelved—four deep shelves, presenting a display of twelve of the most curious masks I had seen since a Venetian collection I valued back in sixty eight. I had been prepared for the sort of thing that you saw at Mayday and other such times—the papier-mâché dragon’s head, the wheat-sheaf mask, the plague doctor and the knight’s helmet, battered out of tin cans, but these…

Each was a superb representation of an animal’s or bird’s head, fashioned with incredible skill. I took up one from the top shelf; it was clearly meant to portray a robin redbreast. If worn, it would cover most of a man’s head. The small black eyes—volcanic glass?—glittered, the short beak was ready to stab, and the lacquer around it as red as arterial blood. I squinted over my glasses, and could see a patina to the lacquer, a series of those tiny cracks which come with age. The mask was made of wood.

“This is surely carved, painted oak, yet it’s so thin, so beautifully crafted. Quite a find.”

Petersen, running his fingers down the mask of a horned bull, agreed.

“Better than I’d expected. Have you any idea how old these are, Mr Beckshaw?”

“As old as the manor?” The man had a look of immense distaste. “They’ve always been here. My father coveted the masks; I hated them.”

“Hard to hate a wooden mask,” said Petersen, but there we differed. The stare of the robin was cold, even aggressive… I put it down.

I have no peculiar talents, but it has often been said that I am receptive to the ‘feel’ of things. Useful in my line of work, because it means I have an eye for forged paintings, and for mutton passed off as lamb. However important—or valuable— these masks were, I did not trust them. An otter’s head had lips drawn back, sharp teeth exposed; the bull was a mask of anger, not placid strength.

“Ritual.” I murmured. “A local custom, some performance at certain times by the villagers and hill-farmers?”

“The Beasts of Kemberdale,” said Beckshaw. “Much of the collection in general was brought together over the last fifty years, but as I said, the masks have been here for generations. They belong to whoever holds the manor. They’re brought out each solstice, and worn in procession around the limits of the dale. It’s a private thing; no outsiders, no reporters or folklorists allowed. I always refused to take part.”

Petersen look blank, poor boy, but dear, clever Margrave could provide.

“They call it ‘beating the bounds’” I said. “Still goes on in various places around the country. Costumes sometimes, and willow sticks—a sort of ritual to remind everyone of the boundaries of the parish or community. Ordnance Survey for beginners—for those with an old-fashioned sense of the land.”

Beckshaw locked the mask cabinet, and going to a small cupboard, pulling out a bottle of whisky and three glasses. He said nothing until we were seated and supplied, the bottle to hand. It wasn’t very good whisky, but the burn of it was welcome.

“So, you hope Erik will take this lot off your hands?”

Beckshaw poured himself a hefty refill. “Those damned ‘heads’, if not the rest. I remember my father taking them down and stroking them—they always frightened me.” His face darkened. “He spent more time with those bloody masks than with his own son. When he died, I wanted to burn them, but when I suggested a good bonfire… well, I started to hear what I took as veiled threats from some of the local people.”

“Burn them? That would be a terrible waste.” Petersen sat on the edge of the sofa, next to me. “They are… magnificent.”

Which is not what you say if you’re thinking of purchasing an item. You point out the flaws, the limited market, the plunging pound—anything you can, including the price of butter and your tragic war wound, to soften up the seller.

“What sort of threats?” I asked.

Beckshaw’s face was redder than before.

“Oh, I don’t know that they were serious, but they annoyed me. The locals are tight-mouthed, short on words. Tight-knit, as well—few enough marry outside Kemberdale. They said things like ‘Would be a bad do for thee, maister,’ ” He shuddered. “It’s like living in a bloody Brontë novel.”

Another whisky, and Beckshaw began to say more of his late father. He was not only the one who had owned the collection which lay in the cabinets, but the one who had amassed it, gathering remnants of Dales traditions as they fell from practice, and nurturing those which persisted. The masks were his beloved centrepiece.

The manor house settled; cast iron pipes complained at the boiler’s demands, and the large room closed in on us. I sipped my drink, feeling an unease I couldn’t shift. I had the sensation that even through an inch of pine, the masks were staring at us—and listening to the waspish sound of Beckshaw’s continued narration…

“…Yet never a word from him,” Beckshaw was muttering. “His own wife—my mother!—for God’s sake. Influenza, fatal, because he wouldn’t fire up the heating, and wouldn’t take her to hospital. They came close to charging him with negligence, but never a complaint from her…”

“So you left at fifteen, and never came back?” Petersen nodded, clearly half-cut. “Well, Beckshaw old chap, I don’t think there’ll be any problem relieving you of all this.”

He took out a notebook, scribbled in it, and showed it to the other man—probably didn’t want me to see how little he was offering for the collection, in case I poked my nose in.

“Fine, fine,” said Beckshaw, barely glancing at what Petersen had written. “It’s all yours. The sooner the better.”

“Why the rush?” I asked.

He scowled. “The Winter Solstice is near. Soon they’ll trail up here, wanting the bloody masks out again, all the paraphernalia of the procession. Just as they always have.”

“It sounds a harmless enough affair.” I thought it odd that, if he felt so strongly about the things, he hadn’t quietly broken them up. Was he more superstitious than he’d admit to us?

Perhaps he felt his father’s spectre peering over his shoulder, not just the disapproval of the Dalesfolk.

“Harmless? Damn the lot of them, and damn my father!”

And then I grasped what was happening. This wasn’t the first ‘vengeance’ sale I’d seen after someone’s death. Not just removing unpleasant memories, but deliberately selling off objects beloved of the dear departed— out of pure spite. By his lock, stock and barrel sale of local history, Beckshaw was getting back at a whole community, as well.

I offered one last mild suggestion.

“Why not simply donate the ‘Beasts’ to the village?” I stood up, my legs stiff from the car. “Call it a bequest from the manor, and then have done with the place.”

“Bollocks,” said our intoxicated host. “I won’t give them the satisfaction of keeping that crap. Kemberdale and its masks can go to hell. I’ll teach them that this isn’t the Middle Ages.”

Petersen merely giggled; I said nothing more.

A few minutes later, the lord of the manor showed us to our rooms on the floor above. Plain rooms, with good beds. Tired, I stretched myself out, trying not to think.

I was sure that something dark was on the horizon…

*****

My companions were quiet at breakfast, which was slabs of gammon, eggs a-plenty and hot tea. I let the food amuse me for a while, and then asked Petersen about his plans. He chewed on the fatty meat and tried to smile. He wasn’t used to hard drink.

“I’ll ring around this morning. Need a haulier from Whitby or Middlesborough—we can’t get that lot in the car.”

It was a sort of plan, immediately scuppered by the fact that the phone line was down.

“It happens,” said Beckshaw. “November’s the devil for storms up here.”

There hadn’t been a storm in the night. I wondered if the November was also the devil for a truculent villager with wire clippers?

“I’ll take a stroll,” I said. “I’m sure it will be fixed soon.”

Why would it be fixed, though? No one else around here had a telephone. I suspected that Petersen might have to drive to some more modern part of civilisation if he wanted to make arrangements.

I have always been fond of Yorkshire. It is, in general, a vast and fascinating county with a vehement sense of its own worth – ‘God’s Own Country’—and a dour suspicion of the South. And of Lancashire, and the Midlands, and… well, you get the picture. Generous in person, and yet insular. Kemberdale was little different from any other small dale in aspect, but as I walked down from the manor and along the main road, I felt I was being observed.

A lone ploughman worked a field by the roadside, a team of horses turning the wet soil, and I thought of the hobby-horse skull in its cabinet. These people were closer to the earth than most, for better or worse. Beckshaw and Petersen had no sense of it, but I—

A stoat or weasel darted across the lane, their scramble followed by a shriek of rooks in the gaunt trees above. And there were wrens in the hedgerow ahead.

“Who killed Cock Robin?” I asked myself aloud and thought of black, gleaming eyes.

I passed a roofless schoolhouse with 1743 carved into its stone lintel, and next to that, a low cottage with a woman sitting outside, peeling potatoes. She paused in her task, her fingernails broken, her fingers caked with mud. Her hazel eyes met my gaze.

“He mun relent,” she said. “We knows as why tha’s here. We all knows.”

I had nothing to offer. “The masks? Not much I can do, to be honest. Mr Beckshaw’s made his choice.”

I thought I caught a glimpse of a face at the window of the adjoining cottage. Kemberdale was definitely watching me.

“T’ain’t his to make. He mun relent, or…”

She went back to her work, making it clear she had nothing else to say.

I, too, thought Beckshaw should relent, and leave well alone. But I didn’t like the sound of ‘or…’

Back at the manor, I asked our host if he had a shotgun.

“Rabbits,” I added, without offering to explain further.

He seemed surprised, but brought down an absolute beauty, with a box of cartridges. A genuine Purdey up and under, twenty eight inch. I silently assessed it as worth seven, eight thousand pounds. To him, it was some casual relic of his father’s time here.

“I don’t shoot,” he said, which was fairly obvious.

If I was wary of the masks, I coveted this gun. A collector’s piece, like a diamond discovered in a coal scuttle. I muttered something about cleaning it, and he lost interest.

The promised rain came, heavy enough to worry Petersen. He looked bleary-eyed.

“Don’t fancy taking the Granada through this. I’ll drive to Whitby first thing tomorrow, and have a chap follow me back with a van. We’ll be out of your hair as soon as we’re loaded, Mr Beckshaw. You have my cheque.”

“One more day?” said Beckshaw, somewhat morose. “But yes, that’s good enough.”

Whilst Petersen spend his afternoon cataloguing the collection, I lay in my room and read or pondered. So Rafael Beckshaw, our friend’s father, had been a typical hard hill-farmer, clearly uncompromising, even cold to his only child. There were no photographs of him, but pages at the back of the huge family bible ran through the generations, scribbled down by successive patriarchs. The earliest entry was 1612. And there was one picture of his wife, taken in the forties or fifties, by her outfit. She looked sad, harried.

The ‘Beasts’ had brought her no comfort, whatever they offered the rest of Kemberdale.

After a dinner which consisted of beef, potatoes and a rambling explanation by Petersen of what he might do with the collection—donations to favoured museums and pure profit-making—I retired early. The rain had not stopped. It had made a lake of the yard; it hammered against the roof tiles, and spoke of nothing good.

I kept the Purdey with me, and wondered why I found myself too often in these awkward, unsettled situations…

*****

The noises in the night were not the house timbers, nor the heating pipes. I had been dozing, above the room where the collection was kept, and was sure that I had heard the heavy main door grate open.

I threw on my jacket, and crept to Beckshaw’s room, the shotgun with me. I shook him gently.

“Beckshaw, there’s someone in the manor.”

His eyes flew open.

“What?”

“Downstairs. There’s someone downstairs. What do you want to do?”

It wasn’t my house, and I doubted that anyone around here meant me any particular harm.

“I want to chase the buggers off,” he said, sliding out of bed and dressing.

I roused Petersen, who had been drinking again and was slow to respond. When he was up, we gathered on the landing.

“They won’t want to tackle three men, whoever they are,” said Beckshaw.

I sighed at ‘whoever they are’. Who would the intruders be but Kemberdale, come either to take the masks—or make a crude and direct point about their disposition?

We went barefoot down the blackened stairs, wincing at every small creak, until we stood before the room which held the collection. Any chance I might have had to urge caution was ruined by Beckshaw throwing back the internal door and striding in.

Oil lanterns stood by the door to the yard, setting long shadows across the room, but my attention was drawn rather to the six figures by an open cabinet. One of them was the ploughman I had seen earlier, I thought; the other five were already masked—the robin, the otter, and the bull; the raven and the boar. I shivered at the sight.

The ploughman stood back, holding a powerful representation of a wolf’s head, whilst other masks lay on the floor.

“They are ours, by right,” said Cock Robin—a man’s voice, muffled but strangely high and melodic. “If we must take them, we shall not be kind –”

Beckshaw lurched forward, but the Bull intervened, slamming into the man and felling him. Petersen gasped, and with the usual stupidity of youth, tried to grapple with the Bull, the largest figure there. That gained him a driving fist to the belly, and the attention of Cock Robin—the beak thrust, and Petersen shrieked, blood running from his cheek.

I am not a man of action. I am slightly overweight, in my middle years, and inclined to favour comfortable seating. I was, however, concerned about how far this would go. I made my own move, mostly to protect Petersen, grabbing at Cock Robin’s mask and pulling it from his head…

There are moments in our lives, moments when our souls take precedence over our clever minds or earnest hearts. Such moments are rare, but this was not my first, and so I stood, rather than ran screaming.

Beneath the mask of glittering black eyes and cruel beak, was… a stark and unexpected sight. From the man’s collar rose a feathered head with eyes of dark ice and a wicked beak, open to show a bird’s darting tongue. The feathers moved gently, alive, with his breathing; he was, undeniably, the mask that he had worn.

I fell back, grasping the Purdey. I knew that I was sober, that this was real—and more, I could smell them now, the warm, musty scent of damp animals, close around me.

One by one the others took off their masks. The Bull, a blunt, over-large head with thick lips and wide nostrils, bovine anger glinting in his eyes—not a man, no, not a man. The Otter, river-sleek and ready, his companions each as their masks made them.

Five beasts stood before us, the Beasts of Kemberdale, and the ploughman, still holding the wolf mask.

“If I were t’wear this,” he said, “I’d be as them. It’s the way, tha sees? Our way to be Kemberdale, an’ keep it as it always were. The Beasts, and the Boundaries, all ours.”

Cock Robin came closer to me, and trilled, called, with a song that spoke of bare hawthorn and tangled hedges; fierce combat, and conquest. Of the short, sometimes violent life of small birds. The Otter barked, and gave me swirling, icy waters—the soft sweetness of a trout caught in mid-leap… and a threat.

This was possession, a possession which went beyond surface appearance, and a terrifying one at that; it reminded me of dear Arthur Keen, now long gone, who had spent time among the Sámi people of Northern Finland, and tried rather too many mushrooms. To wear the skin of the seal was to become the seal…

Petersen moaned, holding the side of his face. Blood ran between his fingers. Beckshaw was blank and bruised, crouched against the cabinets; it was up to me, and I was a dealer as well as a critic. I was used to negotiations. I pointed the shotgun at the hare mask on the floor, not that far from Beckshaw.

“If I fire, the Hare will be shattered, one of your Beasts no more. Lost, gone from Kemberdale.”

Cock Robin shrieked; the Bull grunted, but they held back. That hesitation told me all I needed. I doubted that anyone living had the art to make such potent things again—if they had, this intrusion would not have been needed.

“Two cartridges—two masks. I might even manage to reload, but I don’t want to do this, believe me.”

“Tha’s not frit, not like t’others.” A harsh croak from the Raven. “Tha knows how it mun be.”

Frightened? Well, I might be later, but for now…

“So we understand each other,” I said. “We can make a deal –”

“No!” Beckshaw tried to rise; the Raven turned its huge black beak to him and cawed an obvious threat.

“Steady,” I warned them all. I eased myself to one side and helped Beckshaw up, with the Purdey steady.

“Beckshaw, your father is rotting away quietly wherever he was buried. There’s no vengeance to be gained, no ‘win’ for anyone here if the masks are destroyed. You can sell this place and have a life—back in France, maybe. I don’t know.”

His anger struggled with fear, and with my slow, steady words.

“Be a more generous spirit than Rafael Beckshaw. Let these people be, let Kemberdale keep its ways.”

As his shoulders slumped, the Boar, motionless until now, bent and picked up the hare mask. Whoever was beneath the tusks and bristled snout was female, powerfully built—or was that also a property of what she had donned? She held the Hare out to him—as if to demonstrate that he still had one last chance to join them, to be part of this…

“No.” He turned away, shuddered. “Just take the damned things. Get them out of here!”

Cock Robin trilled, and I watched as they gathered up the rest of the masks from the cabinet, cradling them with care; as they formed a solemn, silent procession out into the night. Would these people be themselves again, by dawn? Which was real, the image or the creature beneath? I had no idea.

The whisky bottle was empty, but all was saved by discovery of a rather nice cognac behind it in the cupboard. Beckshaw was silent; I propped Petersen on one of the sofas, and cleaned with wound, which was long but shallow.

“Could be worse, Erik. He might have had your eye out. Cock Robin is a fighting bird, you know.”

“What… what happened?” He had retreated into himself.

“We were visited. The poor light and jostle of local villagers confused you, and you gashed your face on a door.” I surprised myself by chuckling—a nervous reaction, I suppose. “That’s what I’d say, down the wine-bars.”

The brandy helped my companions drift off to sleep again, and allowed me to sit quietly by the empty cabinet which had held the masks. I had a good friend in Hull—a land agent—who would be able to help Beckshaw shift the Kember Manor estate quickly, if certain aspects of the story were trimmed. Petersen could turn a profit on the rest of the paraphernalia in the other cabinets, and would be able to show off his scar for a few weeks. It gave his long Viking face even more character.

And I? I had lost nothing by the trip, and if Beckshaw wasn’t too mad with me, he might be persuaded to part with the Purdey.

Ah, you will say, but more importantly, I had learned the truth of the Beasts of Kemberdale. To which I might agree, except that what I witnessed had no rational explanation. It is fortunate that, unlike Archie Crane, Justin Margrave knows how to keep his mouth shut.

Outside, in the deep dark of Kemberdale, unsullied by street-lamps or other acts of man, the triumphant song of a robin pierced the night…

(copyright John Linwood Grant, 2023)

And you can purchase the full Lonely Hollows anthology in all formats through the following links:

And you can purchase the full Lonely Hollows anthology in all formats through the following links:

amazon us

amazon uk

2024 will see the publication of John Linwood Grant’s fourth and fifth collections of dark tales, as well as two anthologies he is editing – Alone on the Borderland: The Edwardian Weird and A Darker Continent: Strange tales of Europe at War. His most recent publication is the 80 page novella ‘A Promise of Blades’, which can be found in Sherlock Holmes and The Arcana of Madness (Crystal Lake, 2023):

amazon us

amazon uk