Greetings, O Best Beloveds. Today, as keen supporters of independent presses, we’re pleased to have a special feature on the superb work of Canadian publisher Undertow Publications. We have on offer our own fresh-baked review of Kay Chronister’s collection Thin Places (Undertow, 2020), a reminder of Laura Mauro’s debut collection Sing Your Sadness Deep (Undertow, 2019), and a weird welcome from Michael Kelly himself, the Dark Presence behind these and other cunning volumes (plus some brilliant cover art).

Undertow (n) An underlying current, force, or tendency that is in opposition to what is apparent

So let’s start backwards, as always, and hear from Michael about his press first…

MICHAEL KELLY SPEAKS

We’re thrilled to be featured here at greydogtales. Like greydogtales, we’re endearingly weird. And proud of it.

The boring stuff:

Undertow Publications is a celebrated independent press in Canada dedicated to publishing original and unique fiction of exceptional literary merit. Since 2009 we’ve been publishing anthologies, collections, and novellas in hardcover, trade paperback, and eBook formats. Our books have won the Shirley Jackson Award; the British Fantasy Award; and we are a 4-time World Fantasy Award Finalist.

Blah, blah, yada, yada.

Fact is, we love books and stories. Strange, beautiful, macabre, transcendent, odd, scary, lush, lean, numinous, oneiric, and unclassifiable books and stories. We’re almost exclusively known for publishing short fiction, whether in our magazine Weird Horror, or anthologies and single-author short fiction collections.

https://undertowpublications.com/weird-horror-magazine

“Yeah, but what kind of stuff do you publish?”

“Uh, I don’t know… weird fiction?’

“Oh, that’s my least favourite kind.”

“Oh. Sorry. I guess.”

Our aesthetic is beauty and terror, and we believe a book can be judged by its cover.

Our occasional anthology series Shadows & Tall Trees has won the Shirley Jackson Award, and several stories from the series have been reprinted in various “Best Of” anthologies.

https://undertowpublications.com/shop/shadows-amp-tall-trees-vol-8-paperback

Two more Shirley Jackson Award-winning books — Priya Sharma’s All the Fabulous Beasts and Aickman’s Heirs, edited by Simon Strantzas — continue to sell well for us.

Both are masterfully crafted and will, I’m certain, endure. I mean, at least until my death. Please check them out.

https://undertowpublications.com/shop/all-the-fabulous-beasts-trade-paperback

https://undertowpublications.com/shop/aickmans-heirs

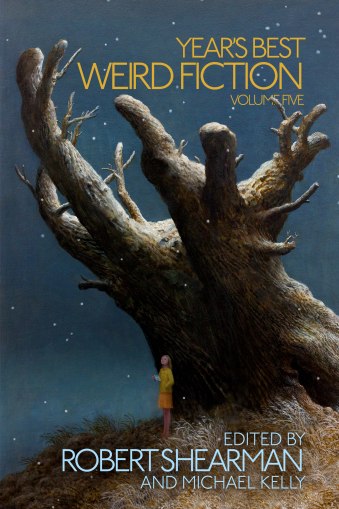

Finally, we’re really proud of what we accomplished with the Year’s Best Weird Fiction.

From 2014 – 2018 we produced 5 volumes, and thanks to our glorious guest-editors it showcased the breadth and diversity of the field. I’m still asked, “What is Weird Fiction?” Who knows? The first 3 volumes are out of print, but you can grab volumes 4 and 5 (which won the British Fantasy Award) still.

https://undertowpublications.com/shop/years-best-weird-fiction-vol-5-trade-paperback

That’s us! Weird. Endearingly so.

Michael Kelly, 1/21

SOME DAYS YOU’RE JUST A READER

(as dictated to a large dog by John Linwood Grant)

There is something odd about hyacinths; I always find their scent disturbing yet intoxicating, their appearance waxily strange, and yet beautiful. Which is, conveniently, how I feel about many of the stories in Kay Chronister’s Thin Places…

I initially picked this one up not as a reviewer or a writer, but simply because I wanted to see what weird fiction was up to. Out of pure curiosity (I don’t read in my own backyard when I’m actively writing, and I must have been drafting some murderous Edwardian shenanigans at the time).

So, without any expectations, I took a half hour off to read the collection’s opening tale, ‘Your Clothes a Sepulcher, Your Body a Grave’. And I thought it wonderful. Truly evocative weird fiction with a certain Gothicism – and an abundance of actual hyacinths in it. I could see I was going to like Kay Chronister. A few months later, I had chance to read the entire collection through in one go, and I had thoughts.

Contemporary weird fiction is the creature which you recognise when it crouches on your chest, but which you can’t always adequately describe to others. Well, the good stuff is, anyway. The poor stuff is just people being too clever, too vague, or raiding the thesaurus.

This is a book which suffers from none of the above weaknesses, with one proviso – many of the stories are about change and transformation, and the exact nature of the change, and what it might generate, is not always spelled out. Chronister brushes you with monstrosities, but doesn’t overplay her hand. It’s not that the stories don’t end ‘properly’, as is sometimes said of pieces of weird fiction, it’s that you are left to ponder. And pondering is important.

Chronister deals with generational relationships, and most of the book is concerned with lineage, especially the core matrilineal nature of the world, mother:daughter and sister:sister relationships, and their consequences. This is not to say that men are necessarily demonised or excluded herein, lest some sensitive boy-readers begin to worry – there are some intriguing male characters as well – ‘Life Cycles’, for example, deals deftly with the desires, needs and dooms of men and women, as does ‘Your Clothes a Sepulcher, Your Body a Grave’.

The yearning to give birth and the consequences of doing so are both explored within. There are touching moments, but many are of transformational horror – what we choose, what we submit to, what we become. Birth creates both victims and monsters; it creates us. The cyclical nature of this process infects the book.

‘Your Clothes…’ is an excellent example, and stories such as ‘Life Cycles’ and ‘Too Lonely, Too Wild’ also stand out. But for me, the single finest story outside of the opener is ‘The Fifth Gable’ where Chronister melds folk-tale sensibilities with the fantastical to great effect (not the only story where a folk/fairy tale grimness lies beneath). Unnamed women in a house with many gables make ‘children’, each in their own way, isolated from the world – and then comes a visitor, who wants a child of her own…

Whilst the mother:daughter axis is a big part of her core material, Chronister is very skilled with landscape and the built world; her stories are rich with psychogeography (geometaphysics, if there’s such a thing?). The very feel of people’s surroundings seeps into you. And at least half of the collection could be described as Folk Horror — ‘The Women Who Sing For Sklep’, set in Eastern Europe, is a particularly strong F/Hish example.

Reviews should not always gush throughout. If I have reservations about any of the contents, they pertain to the title story itself, ‘Thin Places’, which is again finely written, with nice characterisation in the shape of the protagonist/observer, but a little slender underneath, and ‘White Throat Holler’, whose premise doesn’t stand up as well as the writing of it. Even so, neither of these lack their satisfying moments, and would out-run many of their competitors in the overall field.

In short, Thin Places is very rewarding, and well worth picking up.

https://undertowpublications.com/shop/thin-places

https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B083GZRNV7/ref=cm_sw_em_r_mt_dp_VQZYHJCGRE4VRBV82G0K

SING YOUR SADNESS DEEP

An Undertow book which we’ve covered before but must mention again, is Sing your Sadness Deep, by Laura Mauro. It’s perhaps no coincidence that this collection by a skilled female writer of the contemporary weird also concerns itself much with women’s lives and transformation, though Mauro’s wings are spread wide over different landscapes from Chronister’s (the latter is perhaps more claustrophobic and tinged with the Gothic than the former).

At the time we said:

“The debut collection by Laura Mauro, Sing Your Sadness Deep, is a work of fine and accomplished writing, as near to flawless in its execution as you might wish for.”

And that is still true. Again, recommended, as is Priya Sharma’s All the Fabulous Beasts, mentioned by Michael above – another wonderful and rewarding collection.

You can read our full piece on Sing Your Sadness Deep here:

http://greydogtales.com/blog/laura-mauro-sacrifice-and-transformation/

Whilst you’re waiting for your Undertow books, why not have a look at John Linwood Grant’s own recent second collection,Where All is Night, and Starless (Trepidatio 2021). It’s not bad.

AVAILABLE NOW THROUGH AMAZON UK & US, AND THROUGH THE PUBLISHER, JOURNALSTONE

Amazon US: Where All is Night, and Starless

Amazon UK: Where All is Night, and Starless