On the principle that greydogtales is another country, we’re being different again. Today’s feature is an unusual illustrated interview with mathematician, artist and writer Raphael Ordonez. We initially asked the erudite Raphael to join us as part of our weird art theme, but there’s much more to it than that – we slide in and out of fractals, fantastic illustrators, biology and his own fantasy fiction along the way.

As greydogtales is also a grasshopper in that other country, we first came across Raphael accidentally through his blog, Alone with Alone (link at end of interview), and then discovered his interest in William Hope Hodgson. We had to delve further. So here are some thoughts from the chap himself, and some terrific pieces of art.

greydog: Welcome, Raphael. As you know, we’re majoring on weird art and illustration here at the moment. You’ve done paintings from real life and some quite fantastical pieces.

ro: You could say that fantasy illustration is how I got into art. In school I often got in trouble in math class for drawing pictures of monsters and goddesses and maps of imaginary countries instead of listening to the teacher. When I went to college as an art student, it was with the intention of becoming a fantasy illustrator. I can only do that kind of art when the mood hits me, though. That’s probably why I abandoned that idea of a career. Or maybe I’m just capricious.

When I paint from nature, I’m generally going for a purely visual, abstract beauty. The urge to paint something round and red strikes, for instance, and I go find a mountain laurel bean. This kind of motivation has grown up slowly in me over the years. Paul Klee, whose art was very abstract, describes a painter as a tree, drawing material up out of the earth and turning it into a crown of leaves, transforming it in the process. My art is very different from his, but I think he really captured what it’s all about.

In Forms and Substances in the Arts, Etienne Gilson describes the perennial opposition between “drawing” and “painting,” that is, between art as illustration and art as visual beauty. I feel this tension in myself, and continually vacillate between one and the other.

greydog: The first thing we noticed was the strength and clarity of light in your paintings. Is this about personal style, or is it also something to do with the quality of the light where you live?

ro: I like sharp chiaroscuro in most everything in life, including art. Perhaps that’s why I love the Santa Fe area so much. My paintings tend to reflect the high deserts and plains of the American Southwest rather than where I live, that is, the South Texas brush country. Though I’ve been here most of my life, I find the general quality of light uncongenial. Lately I’ve been doing paintings of local legendry from the time of the Spanish explorers, so perhaps the still, sultry air and bright, hazy skies of my environment are starting to sink in at last!

greydog: We assume that you have a naturalist’s heart and eye, given your detailed paintings of insects and plants.

ro: I’m not a trained biologist, but I’ve always spent a lot of time outdoors, camping and backpacking and studying plants and animals, especially insects. I enjoy collecting live specimens and taking pictures with my digital microscope. I also go birdwatching and beachcombing and that sort of thing. Mostly I like to get out where it’s very quiet and watch things grow.

My dad was a science teacher when I was a kid, and one of my favorite toys was an old microscope with which we’d project images of live pond samples on my playroom wall. We also went on collecting expeditions to the gulf coast. My room was a combination museum and menagerie, with pinned insects, seashells, skeletons, fossils, and live animals. I was most interested in insects, and once got a detailed tour of a university entomology department from a doctoral student my dad knew.

Not much has changed in the transition to adulthood. A while back I grew a magnificent colony of Madagascar hissing cockroaches from a single pair. The excess roaches were in turn fed to a pinktoe tarantula, but, unlike Renfield, I stopped the food chain there. My wife made me get rid of them when our first baby came, but now she misses them!

My art definitely reflects these interests. I often paint insects because they fascinate me, but also because they embody so many different shapes and colors, and seem pieced together from distinct components, like clockwork. I gravitate toward cacti and flowers for the same reason. I focus on the small-scale because I like precision, and you can’t be precise with a field of grass or a distant oak. I’ve always had trouble seeing the forest for the trees, and my paintings tend not to have much middle ground.

greydog: And yet that’s perhaps what makes them so striking. You work in both oil and watercolour on a variety of surfaces. Which do you find most satisfying?

ro: I usually work in watercolor when I want to illustrate something, and oil when the focus is color and form. For watercolor I use a heavy hot-pressed paper, as this allows for a great amount of detail. Sometimes I also paint on Claybord, which consists of an absorbent clay ground on a sheet of hardboard. It’s a resilient, versatile surface, and I’ve used it for both watercolors and oils.

Over the years I’ve learned to pay careful attention to my materials, and I enjoy learning about traditional preparation methods and the chemical compositions of my pigments.

greydog: We’d also like to mention your fractal art, which is very striking. Could you give us a simple introduction to that work?

ro: Loosely speaking, a fractal is a figure that falls between dimensions. A smooth curve like a circle or a line is one-dimensional; a smooth surface like a plane or a sphere is two-dimensional. But you could imagine a curve that’s so squiggly it transcends the first dimension but doesn’t quite make it to the second, or so disjointed that it falls short of the first dimension. That’s a fractal.

A lot of fractals (all the ones that appear in my digital art) are produced via an iterative process. For instance, you might begin with a line segment, remove the middle third, and replace it with two of the same length, meeting so as to form an equilateral triangle. You then do that to each of the four segments that result, and so on, ad infinitum. That’s how the Koch snowflake is formed.

I first learned about fractals from a film shown in my college design class. I was so impressed by their beauty that I went out and switched my major to mathematics. Now I’m a university math professor who specializes in geometry (though not fractal geometry). When I make fractal art, I’m doing something that’s quite distinct in my mind from what I do when I paint. It reflects an intellectual rather than an artistic motivation.

greydog: Have you commercial ambitions, such as selling canvasses and prints, or book illustration?

ro: Lately I’ve sold a number of paintings through local galleries, and hope to sell more. It’s painful because I don’t like parting with my work! Up until recently I’d been storing all my finished paintings in boxes and not showing them to anybody. When I sell them I feel that I’m really giving them away and accepting a small honorarium in return for my time. That may seem pretentious, but, whatever anyone else may think of my work, to me it’s priceless and irreplaceable.

In Andrei Rublev, one of my favorite films, director Andrei Tarkovsky portrays different approaches to art and the ways in which art and practical realities come into conflict. The protagonist, surrounded by violence and spiritual compromise, descends into his own personal hell, but emerges with the conviction that art should be “a feast for the people.” And that’s come to be my own mission in life: to provide a feast for the people, to the fullest extent that my personal talents and limitations allow, through my teaching, my painting, my writing, my involvement in the local community.

I am interested in book illustration, though I haven’t illustrated anything but my own work thus far. I would enjoy illustrating the work of some of the older fantasists. Time is a limited resource, though, and it’s always a question of where to invest it. We’ll just have to see what develops!

greydog: We’re always looking for new artists and illustrators to investigate on greydogtales. Who do you particularly admire?

ro: When it comes to my illustrational side, I most admire William Blake and the early work of Samuel Palmer. Odilon Redon is another one of my favorites. His weird charcoal and pastel drawings make me think of Clark Ashton Smith. I’m also very fond of Pieter Breughel the Elder and Hieronymus Bosch. Both strike me as being very much in keeping with the weird horror of William Hope Hodgson, and one Hodgson cover (the Ballantine Night Land) appears to be inspired by Bosch’s depiction of hell in The Garden of Earthly Delights.

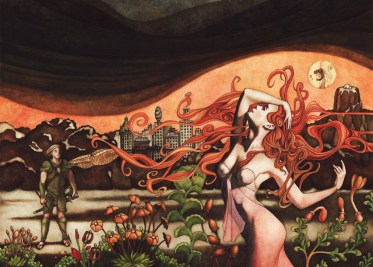

Other sources of inspiration include late medieval illumination, the engravings of Albrecht Durer, the work of earth twentieth century illustrators like Edmund Dulac and Kay Nielsen, and the art of Frank Frazetta. I’m also fond of the cover art from the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, to which the cover painting of my novel Dragonfly is an homage, and the poster art of the film noir era.

When it comes to my more abstract pursuits, I most enjoy Paul Klee, Georgia O’Keefe, Paul Gauguin, and Henri Rousseau.

greydog: You also write fantastical fiction. Mostly short stories, but you do have a novel out. What sort of themes do you explore in your writing?

ro: All of my published stories are set in the counter-earth at the cosmic antipodes (an explanation of which would involve an excursion into topology) and feature Paleozoic life forms, antediluvian races, and supernatural entities based on Greek and Semitic mythology. The human civilization in which the stories take place might be described as Steam Age (but not steampunk!) with Louis Sullivan skyscrapers and Art Nouveau flourishes, and occasional Bronze Age incursions.

My most recently published story, “The Scale-Tree” (Beneath Ceaseless Skies) is mainly about art, and especially the Paul Klee quote referred to above. But in general my stories have to do with man and nature, particularly with the seeming impossibility of preserving a sense of hope or life-purpose in the face of a universe characterized by corruption and entropy and decay and dissolution.

I’m most inspired by older, “pre-genre” fantasy novelists, from Lord Dunsany and David Lindsay down to J. R. R. Tolkien and Mervyn Peake. I also like pulp-writers like Edgar Rice Burroughs, Clark Ashton Smith, and Robert E. Howard. On the science fiction side, A. E. van Vogt, Philip K. Dick, and Gene Wolfe are my favorite authors. My longer works tend to be action-oriented, with a certain hard-boiled vibe, and Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett are frequent sources of inspiration. My short stories owe something to Flannery O’Connor and Raymond Carver.

greydog: And while we’re talking about fiction, you yourself have an interest in William Hope Hodgson, to whom we raised a glass throughout October.

ro: Yes, Hodgson is definitely another major influence, especially through The Night Land and The House on the Borderland. He was clearly motivated by some of the themes I just mentioned. He might be said to have found his own answer to the horrors of a malignant universe winding slowly toward heat death, in the form of a time-transcending erotic love. That’s not an answer that can satisfy me. But perhaps it’s enough for me that he understood the question, which is, I feel, the question of my own life.

greydog: And finally, what’s next for Raphael Ordonez – more fiction, more painting, or both? Do you have a major project on the go?

ro: I have a short story (“Salt and Sorcery”) and a novel (The King of Nightspore’s Crown) in the works, both of which will hopefully be published in the not-so-distant future. The latter will feature another wrap-around cover by yours truly. That’s my next big artistic project.

greydog: Many thanks for your time, Raphael Ordonez.

Fletcher Vredenburgh, reviewing Raphael’s first novel Dragonfly on Black Gate, said:

Dragonfly is the first of a planned tetralogy. In this day of calculated, mass-marketed, trend-following books, here is a self-published adventure, practically handcrafted, with cover, map, and interior art all done by Ordoñez himself. It tells of a young prince let loose in a world of steam engines, complacent aristocrats, and tunnel-dwelling workers, and a social order on the verge of being overthrown. Ordoñez’ style hearkens back to the likes of A. E. van Vogt and Jack Vance, as well as Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Dragonfly is available here (check image in sidebar for UK source):

And do visit Raphael’s website Alone with Alone for more examples of fractals, other art and thoughts on many topics of interest.

Next time on greydogtales: Hm, depends on whether or not I ever finish this cursed Cthulhoid story I’m writing. So either a fascinating new article, or a picture of a longdog chewing a teddybear…

alone with alone

alone with alone

Beautiful, beautiful artwork. I love the Saguaro bloom, and the Taos pueblo, and would happily give both a home.

So glad you like them. He has a great eye for the natural world, doesn’t he?