Time for a quick projects update and to share some news of what’s to come. So in the next couple of days we’ll try to cover all the latest on Occult Detective Quarterly, a forthcoming collection from Mr Linwood Grant – A Persistence of Geraniums, the exciting ODQ Presents anthology, a further planned anthology of classic occult and psychic detectives, and more…

Linwood Nonsense

Let’s get a personal project out of the way first so we can move on – A Persistence of Geraniums. I did writ enuff stories for a general collecshun, I did, too. But this isn’t it. This is fairly specific. It began as a chap-book centred on the titular story, and then got out of hand. Which happened because I realised that I had a range of peculiar tales which went together quite nicely, slightly separate from my main line of post-Carnacki and hoodoo stories. The latter follow a plan going into the 1930s so far; the collection is pure Edwardian.

If you like strange and scary tales, this may suit you. It’s a sort of ‘Tales of the Last Edwardian’ branch line, a collection of John Linwood Grant’s tales of murder, madness, and sometimes the supernatural. The ‘sometimes’ is there because a few of the stories are ghost stories at heart, whilst others are tales of terrible crimes, including the work of Mr Edwin Dry, the so-called Deptford Assassin. Tales of loss, and occasional justice – of a sort. And it was nice to have an excuse to gather together the various stories and observations concerning the popular Mr Dry, as none of them have been in print before.

In addition to Mr Dry, the collection includes two long, brand-new supernatural stories, notes on the period and the concepts, and has an introduction by Alan M Clark, a gifted writer who himself covers the late Victorian period on a regular basis. It also includes a very unusual Carnacki story, of which one reviewer kindly said:

“…This is the first time I’ve read a true first person Carnacki tale. Not only does it succeed brilliantly but, for the first time, I got a sense of Carnacki himself as a fully developed character…”

If that wasn’t enough, Paul ‘Mutartis’ Boswell provides not only a most excellent cover but perfectly nuanced interior illustrations as well. Interior design is by me, but you can’t win them all.

A Persistence of Geraniums should be out in print by the end of July, with luck, published by Electric Pentacle Press.

A Persistence of Geraniums should be out in print by the end of July, with luck, published by Electric Pentacle Press.

Quarterly Occult Detecting

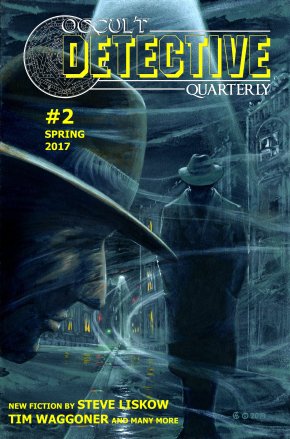

Down to business. Issue Two of Occult Detective Quarterly is available to purchase now – and this time it’s on Amazon, to make availability and distribution easier. It’s a fantastic issue, and we’ve been really fortunate with both writers and artists again.

You can skip this chunk if you’ve already seen the contents list, but if you haven’t, check it out. Inside Issue Two, Steve Liskow brings us a Native American female cop on a nasty case, and Brandon Barrows conjures Carnacki the Ghost Finder, but this is a Carnacki early in his career—and in Boston, USA. Kelly Harmon introduces us to a Catholic, demon-marked girl who takes down demons whilst having to work with a somewhat unusual ‘friend’, and Bruno Lombardi offers supernatural danger for two Fin de Siecle Parisian policemen.

From Edward M Erdelac comes a tale of John Conquer, a cool black investigator in seventies Harlem, balanced by Tricia Owen’s story of a prejudiced American PI getting out of his depth in sixties Hong Kong. And Tim Waggoner’s psychologist-with-a-difference takes on the case of a young woman with nightmares.

Finally for fiction, we present Mike Chinn’s occult adventurer between the wars, accompanied by Joshua M Reynolds’ instalment of our Occult Legion series, set in haunted Scotland. This follows Willie Meikle’s previous tale ‘The Nest’, but is a wild ride in its own right.

On the non-fiction front, we’re delighted to bring you an interview with British actor Dan Starkey, whose superb Carnacki audio was reviewed here last time. Tim Prasil returns, with a most diverting piece concerning the Occult Detective Physician in literature, and our counterpoint is Danyal Fryer’s perspective on the English roots of the comics character John Constantine. Plus we have reviews by Dave Brzeski and James Bojaciuk.

And our artists have done us proud as well. Award-winning artist Alan M Clark provides our cover, plus we have the coolest interiors from ace illustrators Luke Spooner, Mutartis Boswell, Sebastian Cabrol, Russell Smeaton and Morgan Fitzsimons.

Moving Forward

We have a lot to do yet. Here are some of the tasks with which we need to wrestle:

- Subscriptions – As some others have found, meshing Kickstarter subscriptions with a longer term plan isn’t always easy. We began with a simple four issue subscription to pdf and print. Pdfs for #2 have gone out; print is shipping now. But we have new requests for subs, and people who want to extend their existing ones, so we need to tackle that. – the price must be good, we must be able to fulfil each time and so on. Which includes the question of formats…

- Formats – ODQ’s initial concept was for a classic print magazine. But nowadays, eformats are ubiquitous, and easier for some. They’re also good value, and we’ve tried to respond to various requests. ODQ is designed as two-column print magazine, which means that to move beyond pdf, we will have to reformat the entire contents for things like Kindle. We’re going to have a try, which would ultimately mean that the eformat could also be ordered straight through Amazon.

- Issue One – This landmark animal is almost sold out in its print form. If we think it’s worth it, we might put it through Createspace (which has its own problems) in order to make that available on Amazon as a clearly marked Second Edition. The same eformat considerations as above apply.

- Long-term Submissions – One of the questions which comes up with a magazine (as opposed to an anthology) is how to manage submissions which are tempting, but for which you might not have space until two, three or even four issues down the line. With a big company and a long history, it’s probably quite easy. For a small press and part-time editors, not so simple. Don’t forget, a small press can’t usually afford to pay up-front. So do you accept stories without knowing when and where you can use them? Hold them on a short-list, and possibly limit the writer in circulating them elsewhere, while they wait in hope? We want our writers to get the fairest and fastest deal we can manage, and we’re still working on how to speed up and clean up this process.

- Content – We’re still seeking stories based outside the UK and the US, though naturally they have to be damn good as well. In Issue Two we managed to stretch the boundaries. We have hopes of ODQ #3 including more unusual settings, in addition to the obvious core. We actively want diversity of entertainment, with occult detectives and writers of every creed, colour, identity and all the rest. And we still have moments where we’re receiving excellent stories which we can’t in all conscience use, as they’re too far off-theme. Whether or not we relax the edges to bring you any of these is an internal argument – we never set out to be a general weird or supernatural fiction magazine, so we have to be careful.

ODQ Three

Our third issue will be out over the Summer, probably late August/September. We have some excellent fiction already in hand from previous rounds, and have almost filled the issue, in planning terms. That means that we should soon be able to send out acceptances to the best of the short-list, and tell the others if we might be able to fit them in at a later date.

In addition to fiction, we do know that we’ll have another fascinating article by that erudite supernatural story hunter Tim Prasil (with a touch of Dickens this time). We’ll also be presenting a specially written piece concerning Robert E Howard’s ‘occult’ detectives, by Howardian scholar Bobby Derie. Dave Brzeski and James Bojaciuk are on the review trail again, though we might ease their load with one or two other guest reviewers as we develop.

When we open again for new submissions, which will be widely announced in the Summer, we’ll be looking for contributions to Issues Four and Five. We’re talking to those talented artists George Cotronis and Sebastian Cabrol about possible covers, and we’ll be looking for interior art to complement the stories as usual.

Phew!

Tomorrow or Wednesday – Part 2, with news of the ODQ Present anthology, due this Autumn; an exciting publication planned for early next year; the concept of ‘Hell’s Empire’; less John Linwood Grant (hurrah) and more news. Don’t forget that you can sign up simply by email (top left) if you want to be kept up to speed – and no sales-dogs will call…