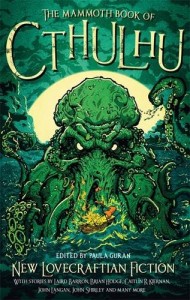

Welcome, dear listener, to our final Lovecraftian feature of the weekend. Today we mark the recent release of The Mammoth Book of Cthulhu, with exclusive commentary by authors John Langan and Michael Wehunt on their contributions to the anthology. And after that we bump into Bobby Derie’s Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos, more of a reference book but no less interesting. Both books might be called post-Lovecraftian, but in quite different ways. Oh, and we drift off into HPL and Hamlet later, but that sort of thing happens here…

We’ll start with Paula Guran’s new anthology of recent fiction by a terrific range of writers – The Mammoth Book of Cthulhu. Paula is senior editor for Prime Books, and edits the annual Year’s Best Dark Fantasy and Horror series as well as other anthologies. Her work has won many plaudits – she has twice received the Stoker Award and twice been nominated for a World Fantasy Award. In her introduction to TMBoC, she says:

What I term “New Lovecraftian” fiction seldom attempts (although it does occasionally) to emulate Lovecraft’s writing style – a style that’s faults are, admittedly, many. Written with a fresh appreciation of Lovecraft’s universe, its writers do not imitate; they re-imagine, re-energise, renew, re-set, respond to, and make Lovecraftian concepts relevant for today.

New Lovecraftian fiction sometimes simply has fun with what are now well-established genre themes. Authors often intentionally subvert Lovecraft’s bigotry while still paying tribute to his imagination.

Yesterday we featured Dreams from the Witch House, edited by Lynne Jamneck (see voices from the witch house), and three of the writers from Witch House are also represented in this collection – Caitlin R Kiernan, Lois H Gresh and Amanda Downum – alongside other familiar names such as Laird Barron, Michael Shea and W H Pugmire.

Long-time listeners will know that this isn’t a review site, though we admit that we are enjoying the anthology. We thought that rather than rattle on, it would be more interesting to hear from a couple of TMBoC’s contributing authors. We were therefore delighted when John Langan and Michael Wehunt kindly agreed to say something about their stories especially for greydogtales. Both, purely by coincidence, reference music, and both give insights into the tales they spun for the collection. Here they are, for your listening pleasure…

Notes on “Outside the House, Watching for Crows”

John Langan

I wrote roughly the first half of this story six or seven years ago, possibly a little more. Up until this point, I had studiously avoided writing about adolescents, in large part because so much horror fiction focuses on this age bracket (think Something Wicked This Way Comes, It, Shadowland, A Boy’s Life, Ghoul, etc.) and I wanted to distinguish myself by doing something different. But I had an idea I would write about music, about a cassette tape whose songs come to inhabit the listener’s consciousness. And for reasons I’m not certain of (my twenty year high school reunion, which I’d skipped but was still in my mind?), when I started writing the story, it was about the tail end of my junior year in high school. I powered through the story until the narrator attends his junior prom, and read most of what I’d written at that year’s Readercon—after which, my friends who’d come to the reading asked me what came next. I told them I didn’t know: I was still writing the story.

In fact, I would be writing it for the next half a dozen or so years. Beyond what I’d already set down, I couldn’t work out where the story was supposed to go. I knew the weird tape the narrator was listening to, the music that had become his personal soundtrack, was going to lead him somewhere, but I could not work out what that destination was. So I pretty much left the story to percolate, returning to it every now and again to tweak a word choice or sentence, waiting for the Fornits to work out the rest of it.

This didn’t happen until I finished my second novel, The Fisherman. There’s a long story in the middle of the book—a novella, really—which involves some pretty far out stuff, including an old, frightening city on the shore of a black ocean, whose police force is not quite human. In the process of writing several other stories (including “Bor Urus,” “Mother of Stone,” and “Shadow and Thirst”) I had found connections between them and the material of the novel, particularly the neighborhood of that city.

When Paula Guran invited me to contribute something to the Mammoth Book of Cthulhu, I thought about that unfinished story and realized that the answer to its second half lay in The Fisherman and those other stories connected to it. There’s no need to have read any of the other stuff to appreciate this story (honestly, even if you do go through it all, it’s as much a series of hints and suggestions as it is anything more coherent at this point). What that material did was provide me a way to reflect on the desire—so strong in adolescence, but not absent from the rest of life—to break out of this existence, to find a way to something else, something different, something (maybe) more. Sometimes, the answer to the challenge you’re facing now comes from something you haven’t done yet.

####

Notes on “I Do Not Count the Hours”

Michael Wehunt

When Paula Guran asked me to write a story for The Mammoth Book of Cthulhu, I fainted. When I came to, I started thinking that I wanted to use music as the backbone of what would become “I Do Not Count the Hours.” I also wanted some creepy video footage, and I wanted to use a main character Lovecraft would not have approved of.

I wanted this latter because Lovecraft’s protagonists tended to be academics and men of science. Invariably white men. Ada Blount is a young black woman, short and petite, a deeply sheltered and codependent woman. And the story is entirely about her. She plays music, and in light of Lovecraft’s views, I thought the viola was a good choice, as it is the forgotten sibling of the famous violin and cello. But it features in nearly every string quartet, and it is just as essential.

My intent was not truly to address Lovecraft’s racism in this story. Others have done so wonderfully. I really only tried to give a voice to someone he would not have given a voice to. Otherwise the story just wants to be creepy as hell with a little beauty in the darkness. Several months later I would write a brother to “I Do Not Count the Hours.” It’s called “Drawing God” and it will be published late this year, I believe. There are slight parallels between the two stories, a sort of shared world, but in this newer story Lovecraft himself is brought more into the foreground, and I’m not particularly kind to him. Writing this second story exorcised my thoughts on the matter.

But he did give us a deeper fascination with the cosmos and our granular role in it, and for all his unforgivable warts as a man, his fiction does live on for a good reason. I don’t think cosmic horror will ever truly leave my bloodstream, and he’s an indelible part of it.

As for Ada, she has had a hard life. A singular life, really, and the way she grew as a character and as a woman fascinated me as I wrote the story. She was raised to be weak, and she grows strong. She goes deep into the woods and does what no one else can. Erich Zann wouldn’t have been up for it. Let that be a lesson to Howard’s ghost.

Meanwhile, I still get a little shiver when I think of those video files on that computer…

####

We thank our talented contributors, and point out that you can pick up TMBoC right now:

As we said on Friday we’re not academics, but we do like to delve deeper sometimes. A number of times we have turned to a very helpful fellow, Bobby Derie, for original material on HPL and his circle, including extracts from correspondence, so it seemed appropriate to mention his book Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos (2014) in this medley about Lovecraftian books.

We’ll quote from the blurb, because it seems silly to rewrite it:

In this pioneering study, Bobby Derie has presented an objective and scholarly analysis of the significant uses of love, gender, and sex in the work of H. P. Lovecraft and some of his leading disciples. Along the way, Derie treats such matters as Lovecraft’s relations with his wife, portrayals of women in his work, and the question of homosexuality in his life and work. Many Lovecraft stories are subject to detailed examination for their sexual implications.

There are two aspects of this substantial and fascinating book which we like in particular. Firstly, it’s meticulously researched and draws on genuine source materials as opposed to collating third-hand opinions just to stir things up. Secondly, it’s not an attempt to create one of those cod-psychological studies of Lovecraft – you can make your own mind up about what Derie presents, and there’s plenty of thought-provoking stuff.

Examination of Lovecraft and his work in such a context does raise some fascinating issues, so it’s helpful that this book includes further material on sex, gender and the mythos in the works of later writers. It’s an absorbing read.

Back here in our less-than-expert kennel, we find it hard to get away from the fact that Lovecraft appeared to have a bee in his bonnet about inter-breeding and miscegenation. It’s as if he feared the Outside breeding its way in to ‘normal’ society and ‘decent’ people – through blasphemous couplings with entities (The Dunwich Horror), through incestuous practice (The Lurking Fear) and through miscegenation (The Shadow over Innsmouth and so many more). The frequency of ‘unholy’ unions, be they with gods, Deep Ones or Polynesians, in his stories, and his dislike of what he saw of as mixed-race peoples, seems in retrospect to be less a matter of prejudice and more an obsessional issue.

It’s easy to despise his views on some areas of life (and right to reject them). We’re not great proponents of needless therapy, but at times we feel sorry that he had to carry such thoughts in his head for so long. Still his fiction prospers, we still read it, and some of it is jolly good.

But that’s only our passing pennyworth. Our other worry is that lurchers, who only exist because of a particular aspect of cross-breeding discovered centuries ago, may not have won his approval.

Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos by Bobby Derie is available here:

As one of our many asides, we were moaning about the ditherings of Hamlet during our interview with SFF writer John Guy Collick (see a colossus of mars)a few weeks ago, and John commented at the time:

Watch the Russian film of Hamlet directed by Grigori Kozintsev… That’s how the play should be done, not as an introspective study of a procrastinator with his head up his bum but as a vast, brooding Piranesi-esque Gothic tale of politics, double dealing and passion.

Bobby Derie subsequently provided us with something we’d not come across before – HPL’s views on the Prince of Denmark. We extract a section because, well, it’s interesting:

I find in Hamlet a rare, delicate, & nearly poetical mind, filled with the highest ideals and pervaded by the delusion (common to all gentle & retired characters unless their temperament be scientific & predominantly rational–which is seldom the case with poets) that all humanity approximates such a standard as he conceives. All at once, however, man’s inherent baseness becomes apparent to him under the most soul-trying circumstances; exhibiting itself not in the remote world, but in the person of his mother & his uncle, in such a manner as to convince him most suddenly & most vitally that there is no good in humanity.

Well may he question life, when the perfidiousness of those whom he has reason to believe the best of mortals, is so cruelly obtruded on his notice. Having had his theories of life founded on mediaeval and pragmatical conceptions, he now loses that subtle something which impels persons to go on in the ordinary currents; specifically, he loses the conviction that the usual motives & pursuits of life are more than empty illusions or trifles. Now this is not “madness”–I am sick of hearing fools & superficial criticks prate about “Hamlet’s madness”. It is really a distressing glimpse of absolute truth. But in effect, it approximates mental derangement. Reason is unimpaired, but Hamlet no longer sees any occasion for its use.

Whether or not this is also a reflection of Lovecraft’s view of himself, and of some of his protagonists, we leave to cleverer people than us poor mutts.

Finally, as the I that is greydog supposedly runs this site, it would be foolish not to mention that I also have what Paula Guran might call a “New Lovecraft” story in the recently-released Cthulhusattva: Tales of the Black Gnosis. This is a cracking collection of dark and thought-provoking tales about the real nature of those who accept the Mythos into their hearts, edited by Scott R Jones – writer, editor and overlord of Martian Migraine Press.

Cthulhusattva is currently riding high in the Horror Anthology charts, and I don’t think that you’ll be disappointed by it – but I would say that, wouldn’t I?

Over the next week or so, we’re back to lurchers, weird art, Victoriana, Dracula and lots of things which are decidedly non-Lovecraftian…

arabian nights

arabian nights