After our recent South American adventure, we lurch surprisingly north. Come with us now to Scandinavia and see the work of Danish artist, Jørgen Bech Pedersen, who produces terrific interpretations of those dark creatures which skulk in Nordic folk-lore.

greydog’s own introduction to Nordic folklore, decades ago, was through many un-related sources: the Marvel Thor comics (not always accurate, funnily enough), bits of Alan Garner‘s Weirdstone of Brisingamen, and Jacqueline Simpson‘s marvellous book Icelandic Folktales and Legends.

Living in a small community by the North Sea, we had a natural feel for those stories. Seal rocks at the bottom of the cliffs – were those really only seals down there? And what actually came in with the sea-frets which washed over the fields? Our ruined chalk farmhouses weren’t so far from those of folklore books, after all.

When we moved inland, years later, other Yorkshire folk would say that our accent was half Danish. So it was a pleasure to discover the work of ‘Bech‘, who agreed to be interviewed for this very programme (all paintings/drawings should be clickable for a larger version, by the way)…

greydog: Welcome to greydogtales, Jørgen – you are our first Scandinavian guest! We initially noticed your work on-line through your bestiary of troldfolk. Is your involvement in folklore a recent thing, or something from your youth?

jørgen: My fascination with folklore is a recent thing that started about 8 years ago. But I guess it really began in my childhood as a fascination for fantasy and fairy tales. At some point I discovered Dungeons & Dragons which further sparked my fascination. But I was aware of the difference between the elves depicted in popular culture and the ones I’d heard about in folk tales. I remember always wondering : why do Danish elves have a hollow back? I had also heard H C Andersen’s fairy tale The Elfin Hill in which the hill opens up and the elves pour out of it. But how?

These questions stayed in my mind for a long time until, at one point, I sat down to figure out the secret behind hollow elves and elven mounds that rise up on four glowing pillars of fire. Once I started reading folk tales, I was hooked. Luckily, I work in a library that keeps a nice section on folklore. When I started digging, I found more and more literature in our archives. I noticed that the majority of literature was quite old. Furthermore I found that folklore illustration was often put together from serveral artists and therefore inconsistent in style and expression. These things gave me an idea to make a bestiary and illustrate all the creatures myself.

greydog: Is there much interest in Danish folklore in Denmark itself?

jørgen: Not in general. There’s been a handful of new fantasy books that focus on folklore and we have seen a couple of small scale Nordic movies that deal with the subject (Huldra – Lady of the Forest and Troll Hunter)

greydog: The Troll Hunter film is superb, and most unusual in its take on the subject. One of greydog‘s fiction projects for 2016/17, The Children of Angles and Corners, is about the re-emergence of huldrefolk or huldufolk. Tell us something about the nature of troldfolk, as depicted in your art.

jørgen: When I made troldfolk.dk, I set out to make a bestiary, or field guide, to all of the folklore creatures of Denmark. What that means is describing the traits and abilities of each creature – their nature, if you will. That was a hard job, because the literary sources don’t classify each type of creature very consistently. Furthermore, to visualize my bestiary, I also had to bring each creature out into the open and draw them top to bottom on a blank background. Again the sources aren´t very helpful. Details are sparse and inconsistent. So again I had to try and capture their look and draw each creature my own way. The field guide therefore, presents over two dozen Scandinavian folklore creatures, that are each cleary documented and visualized. In that way it can be useful as a tool for fiction writers or for implementing these creatures in roleplaying games or computer games.

Choosing this perspective for troldfolk.dk also meant that you lose some of the original mystery concering trolls and fairies the way they were traditionally perceived. Don´t forget that these creatures were very real to farmers in the 19th century. Not just children but grown ups actually believed in brownies, ghosts and elves. Traditionally, there are some general traits about their nature. They were most often perceived as dangerous and something you should avoid dealing with. Elven maids look beautiful. They dance and sing in the fields at night, but if you join their dance, you may die. Other folklore creatures are benign or even helpful if you treat them right. Some of them are mortal and they grow old and die like normal people. Other creatures are more similar to ghosts and the undead.

greydog: You told us recently that you have been looking into British folklore as well. What areas interest you?

jørgen: I want to look more into the differences and similarities between the fairy world of the British Isles and Scandinavia. When I set out to study folklore, I thought the Danish creatures would be very unique to Denmark. That wasn´t the case. Folklore is subject to cultural exchange across borders. Just look at dragons. But especially I want to learn more about the British tradition of the fairy court. One of the things that fascinate me about British fairy lore is the strong ties between the fairy realm and human souls and the afterlife. I belive that idea is far more widespread in your area.

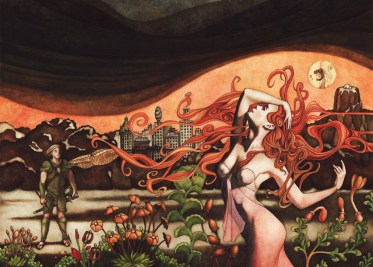

greydog: Your fabulous illustrations are how we spotted you. Which artists do you feel have influenced your style?

jørgen: I have a lot of influences of course. I´m very fascinated by the old Nordic illustrators of the 18th century. They really conceptualized the look of the Nordic trolls and their style is carried on today. Look at Theodor Kittelsen or John Baur. Modern inspiration inclues Brian Froud, Iain Mccaig, Tony Diterlizzi, Paul Bonner and Justin Sweet. Hmm, I could go on. Must make a list on my website.

greydog: And although we know a couple of those, including Brian Froud, we must look some of the others up. Could tell us a little about your painting techniques?

jørgen: The illustations for troldfolk.dk are all hand drawn and colored digitally. Recently I chose to work in traditional media again and I use ink, watercolor, guache and acrylics. I´m really not set on a specific style. I like to try out new materials and styles. Just take a look at bechart.dk

greydog: We know that you accept commissions. Do you have serious commercial ambitions for your artwork, such as a printed bestiary, or is it mostly for your own pleasure?

jørgen: For me art is first and foremost a pleasure but I’m also dead serious about it. I accept commissions that I feel are in tune with what I want to do. Originally I wanted to make a book, but I decided to make a website to reach a broader audience. My goal has always been to inspire people to learn about Nordic folklore and to that purpose a website is more useful. However, I´m still planning to supplement the website with a printed book at some point. This will include a lot more illustrations of each creature and hopefully show them in their proper surroundings.

greydog: Folklore is a major source for fantasy literature. Do you read fantasy or weird fiction yourself?

jørgen: Even though I´m a librarian, I don’t read a lot. I use most of my spare time drawing and when I do read, it´s mostly non-fiction, folklore sources or sometimes a piece of classic literature. I read slowly, so I have to be picky. I do enjoy fantasy a lot and I´ve read Tolkien, the Dragonlance saga, Beowulf, but also a lot of Poe and I´m fascinated by Lovecraft’s dark universe.

greydog: Good man! One question out of curiosity – in recent years, Scandinavia has become renowned for what many call ‘Nordic noir‘, in books and films. Denmark is often thrown in with Norway, Sweden and Iceland, as if they were similar. Is this fair?

jørgen: I’m not bothered by it. There’s a Nordic kinship that I appreciate. I dont feel Danish identity is in any way threatened by this generalization.

greydog: And finally, any plans for your art in the New Year? More bestiary entries, or something new?

jørgen: I’m hired in to do some concept art for a game production and that will probably keep me busy for a while. Can´t tell you anything about it yet, though. Besides that my plan is to do a lot of art, prepare exhibitions and try and sell some 🙂

greydog: We wish you much luck with that and thank you, Jørgen Bech Pedersen. As mentioned, you can find the Bech Bestiary here:

For each illustration in the bestiary, there is also a text piece which is well worth reading. Don’t be put off if you don’t speak Danske – we merely copied the text and pasted it into the google on-line Danish to English translator. It’s not perfect, but there’s lots of great information there. And Bech’s art in general is on-line here:

####

That’s probably the last of our ‘Weird Art’ theme for 2015, but it will return next year. Do keep tuning in – greydogtales continues over the festive season, thought perhaps in a slightly more random “surely I didn’t drink all that brandy” manner…

Haunter of the Dark US

Haunter of the Dark US

alone with alone

alone with alone