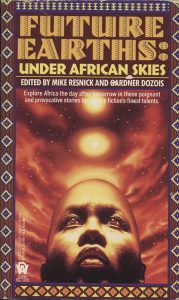

Horror fans and lurcher lovers may ignore this post -it’s about speculative fiction, Africa and Hemingway. I picked up an SF anthology yesterday, second-hand, that has me puzzled. I think it would have had me puzzled when it came out in 1993, but I missed it back then. It’s called Future Earths: Under African Skies (DAW) edited by Mike Resnick and Gardner Dozois. And it’s going to take me a moment to try and explain myself, because this is a musing on editorial choices, speculative writing, and a single book. It’s one of those days when I write what’s on my mind, which is never wise, as I should have learned by now.

(On the plus side, it also makes me note how far we’ve come in the last twenty five years, which is a Good Thing.)

There are a number of issues here. And to confuse you, I’m not going to comment on the fiction itself. The vast majority of the stories are from the mid eighties to early nineties. You have notables such as Kim Stanley Robinson, Bruce Sterling, Naomi Mitchison and Mike Resnick himself (twice), amongst others. I still hope that a number of them are decent, and interesting. What surrounds the stories is the puzzle.

If it were not for its trappings, I would have said ‘Oh good, someone considering African SF back in the nineties. Neat idea.’ I’m not a fanatical revisionist when it comes to fiction, though I might occasionally be critical. People wrote what they did back then, and I try to think about context, though 1993 isn’t exactly deep history.

However, when I got the book back home, I looked at the author list, and I read the introduction and recommended reading list at the back…

The Authors

As far as I can tell, not a single one of the fourteen authors included is black. I’m not saying that a white American or British author can’t write SF about, drawing on, or set in, Africa. It’s entirely do-able, if researched and treated with respect. But I am puzzled as to why you would produce a specific anthology sub-titled Under African Skies, and not include even one African or African diaspora author.

It’s not like there weren’t any such writers in 1990s science fiction. Did the editors look for such work? Did they offer opportunities, and get rebuffed. I don’t know. I do know that in the old days when I picked up various SF anthologies linked to Russia, for example, I did expect to see some Russian authors in there. Yes, Russian speculative work has deep roots, but still…

The African experiences of Mike Resnick, a seasoned and award-winning writer, are mentioned on Wikipedia:

“The other main subject of Resnick’s work is Africa – especially Kenya’s Kikuyu history, and the culture of Kikuyu tribes, colonialism and its aftermath, and traditionalism. He has visited Kenya often, and draws on this experience. Some of his science fiction stories are allegories of Kenyan history and politics. Other stories are actually set in Africa or have African characters.”

I have absolutely nothing against the chap – I don’t know him as a person. It may well be that he thought having such an anthology at all, focused solely on SF and Africa, was an achievement – and I could see that as a point. Perhaps it was a fight to get it published. Who knows?

The problem is that we “explore Africa the day after tomorrow” in the company of… well, no Africans. And we are brought into the nature of the anthology in a very strange manner.

The Introduction

If I was African, I don’t think that I’d be bowled over by this, quite honestly. I’m not happy with it as an old white Yorkshireman, if that tells you something. The introduction includes a list of six examples of atrocities or arguable practices in relatively recent African history, all committed or practised by native Africans. These are posed as the actual or potential inspiration for SF stories.

Apart from issues of taste, the most surprising point is that it mentions no example of the dreadful atrocities committed by Europeans, which, if you’re heading in that direction, could inspire a thousand harrowing speculative stories. Very few of which I’d want to write, but at least I know about them.

Snippets on Somalian slavery, Idi Amin and ‘Emperor’ Bokassa are a strange way to introduce an SF book. They seem meant to demonstrate how ‘alien’ Africa is. The sixth example cited sent me on a different trail altogether.

“There is no word for ‘woman’ in Swahili, the lingua franca [of East Africa]. The closest one can come to it is ‘manamouki’, a word that means ‘female property’, and equally describes women, mares, sows and ewes.”

Now, languages are odd creatures, with many constructs which have multiple meanings, or come from outdated roots. It happens in European languages. I occasionally flirt with Swahili, because of one of my characters, and I wasn’t certain about that statement by the editors. So I had a look into the matter. I could be confused, but this is my understanding:

There are perfectly good words for ‘woman’ in Swahili. Mwanamke is one, or jike ‘lady’. And you can find mwanamke in sources well before the early nineties – nor do you need to go to East Africa. Just to give one simple example, there’s a 1967 book on traditional Swahili poetry, current around when the editors were building their careers, which reports the word in verse.

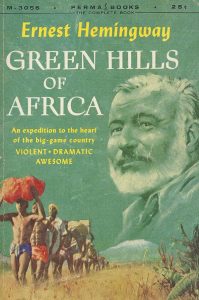

I can find no English translation for manamouki. Resnick himself used it as a story title, and a number of times inside his fiction, so where did he get it from? Did he hear it in a Kenyan marketplace? The obvious connection is to Ernest Hemingway, who used the word in his book Green Hills of Africa. The problem here is that Hemingway’s Swahili was a mix of outdated dictionaries, pidgin and things he seems to have made up. It’s back to the old jokes about English-French dictionaries written by a Portuguese author who knew neither language.

I followed this idea, and came across Martin Walsh’s East African Notes and Records site, which has a specific entry on Hemingway’s dubious Swahili. Well worth a read:

http://notesandrecords.blogspot.co.uk/2010/10/bad-swahili-and-pidgin-swahili-in.html

Essentially, outside of Hemingway and then Resnick, manamouki doesn’t appear to exist. My most charitable thought would be that it comes from some East African pidgin that someone picked up. It would be nice (though unlikely) if some Swahili speaker read this and put me straight.

The examples are followed by the question “Is there anyone out there who still thinks Africa isn’t alien enough?”

Clearly, the introduction was written for white, Western SF fans, to get them interested. But I found it hugely off-putting. Not a single mention of black writers or creators. There may not have been many examples for the editors to latch onto easily, but Octavia Butler, Samuel Delany and Charles Saunders were writing in that period, to name three notables. Or what about a comment on how it would be interesting – and productive – if more black writers actually in Africa were embracing SF. Nope.

I was in my thirties at that time. I was a trainer in mental health issues, and had already, at least four years before, participated in training which discussed the crucial nature of listening to non-white viewpoints and experiences to make sense of things. Another contextual point – the year after the anthology came out, in 1994, Mark Dery used the term ‘Afrofuturism’ in his essay ‘Black to the Future’ when talking about underlying themes in African-American science fiction, music, and art.

Nor, in passing, was I greatly moved by the early statement in the introduction that “This is an anthology of science fiction stories about that exotic and mysterious continent.” Which sounds very 1920s to me (in 1993, the year this anthology came out, Nelson Mandela was addressing the British Houses of Parliament).

“Further Reading About Africa”

I did have hopes for the reading list at the back, but this too was to puzzle and disappoint. A list of fiction by white, non-African authors such as Fredrick Pohl and Robert Silverberg; ‘source’ books on Africa such as Elspeth Huxley’s 1935 White Man’s Country, written nearly sixty years before hand and tilted, despite some of its virtues, by 1930s colonial thought.

End Musings

In conclusion, I’m torn between the editors’ obvious interest in promoting speculative fiction which might have seemed very different and exciting to early nineties SF fans, and the strange and occasionally woeful shortcomings of the book-as-concept. I make no criticism of the authors within – their stories may be great SF. I can even conceive of some publishers of the day being unwilling to fund the book unless it had big known white names in it. Not sure that that excuses the introduction, though.

What I’d like to think is that we couldn’t and wouldn’t do this today. There are now many terrific African and African diaspora speculative fiction writers (no, I’m not going to do a list – look it up). I’d love to see the shape of Under African Skies remade, with informed editors selecting the best Africa-linked SF. There might be such a book, and if there is, someone should tell me. I’m usually awash with too much weird fiction to read, and miss a lot of stuff.

(This post from last month mentions black creator SF, but it’s mostly from an American slant.)

I’m willing to be told that I’m wrong about the anthology – that the quality of the contents vastly outweighs the nature of the introduction and framework. But don’t push the point about this being way back in 1993 too much. It was possible to do better, even then. I certainly wouldn’t have written a training manual on mental health in Africa without any actual African contributions. That would have been silly.

(If you’re a huge Resnick fan who feels outraged, don’t bother with any vitriol. I didn’t go for the guy – I even looked at reasons why the situation might have been so. Reasoned points – yes. ‘How dare you?’ – no thanks.)

Note: I used ‘Afrika’ in today’s title as an illustration. For some, there is a point to using K rather than C. The arguments for this vary. There are those who state that Afrika is a more common spelling in many of the actual African languages, and that the C became predominant only through colonial terminology. I’m not a linguist, so unable to debate that further. I do know people who prefer the use of Afrika as a position statement, through which those native to the continent, and those voluntarily or forcibly separated from it, can make a positive point about their own sense of identity and ownership. That the continent and its peoples are theirs to name, not someone else’s. Sounds reasonable to me.

Opinions over. In a couple of days, some lighter relief, so don’t go away. If you know greydogtales, you’ll know that these things happen now and then…