Writing about Africa. Slightly psychotic ponies. Mythos fiction. Weird fictional roots. We are responsible for little of what follows – but it appears to include an awful lot of words from John Linwood Grant. For here at greydogtales we find that even we are not immune to the latest fashions and trends. So today we welcome a guest interviewer – the handsome, intelligent, and adequately tall S. L. Edwards (er, we’re not sure we wrote that line). S. L. Edwards has conducted all sorts of interviews in the past, but this is his first time interviewing a fellow author. Well. Let’s just see how he does…

THAT LINWOOD BLOKE

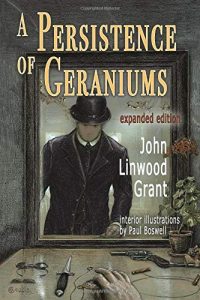

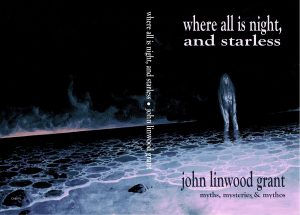

sam: Thanks for being here, John. Your second collection Where All is Night, and Starless is a bit of a departure from your first, A Persistence of Geraniums. Some readers have no doubt come to identify you with your Edwardian stories and its mythology. What common DNA do you see across your two books?

john: My late Victorian/Edwardian tales interconnect more than most, and are well suited to hanging around with each other. Most of them belong in one way or another to my Last Edwardian cycle (like a real velocipede, but on paper). Where All is Night is more eclectic, with quite a bit of what might be called ‘contemporary weird’ in it, and folk horror. As far as I’m concerned, the stories in both are still about people dealing with odd or appalling situations; I find the Edwardian period fascinating, but the base elements of humanity are there in any period. Only the circumstances, sometimes more extreme in this new book, have changed. Less geraniums, though.

sam: You and I have talked often, and one thing I absolutely envy is your ability to write so many different types of stories. You’ve attributed this to being a “jobbing” writer, but I think there’s more. You certainly don’t get this good without practice. Tell us about this practice. How did a young John Linwood Grant become so interested in horror, humour, and Sherlock Holmes? What are some of the earliest stories you remember writing and where are they now?

john: I had no practice in writing short stories, novelettes or novellas at all until I first tried writing them five or six years ago. I had, however, drafted chunks of some huge, over-complicated novels in the nineties, ploughing away at night after work. I’m not even sure I understand them myself on the few occasions I glance at old chapters from them. They were a bit impenetrable, for the most part. But you might call those ‘practice’, in that I conjured an awful lots of words to no great purpose.

The only real survivor of the early stuff is a partial work which inspired the Last Edwardian stories – and that sprang from years of being purely an avid reader of strange fiction in the seventies and eighties. I was a precocious youth and a fast reader, so devoured such stuff, especially when set from the 1880s to 1930s. Hence Conan Doyle, Algernon Blackwood and M R James influences, probably, but also William Hope Hodgson, who inspired my deeper interest in weird fiction. Add touches like the dry (or wry) humour of Jerome K Jerome, the Grossmiths, and Saki, and there I was. Doomed. It all sounds a bit British, doesn’t it? Hmm.

sam: And the lurchers, John? What of the lurchers? What is it about those long, shaggy dogs that appeals to you so?

john: I think it’s a feeling that comes over you, or doesn’t – something about them that makes certain people lifelong devotees or enthusiasts. I didn’t know I was one of those people until our first lurcher, and getting more lurchers just made it worse (or even better, if you know what I mean). In practical terms, they’re incredibly fast and amazing to watch when they run, but also terrific companion dogs, returning love for love. When they’re not zooming, they can be very laid-back, and all ours have been been superb ‘family’ dogs. I wouldn’t be without them.

sam: Turning back to the book, you made the bold decision to include a comma in the title. Beyond that, you actually open the book with a selection of Mythos stories. Your experience with Lovecraft, if I recall correctly, is quite different than mine. Tell us about how you came to write mythos, when you yourself were not so interested in the mythos?

john: I gripped that comma with the heart of a bitter and vengeful lover. But the Mythos… Lovecraft was never a primary interest for me (although by the end of my teens, I’d read just about everything he produced). Even back then I preferred Hope Hodgson, as above, and perhaps Clark Ashton Smith as a ‘weird’ writer, but I was aware of HPL’s impact on others, and acknowledged the power of some of his imagery and ideas. Only ‘At the Mountains of Madness’ really moved me, and the reason for that is something I finally got to cover in ‘Strange Perfumes of a Polar Sun’, which is in the collection.

When I entered the writing market, as it were, I had only post-Hodgsonian roads planned, but then (as you might know) I saw Scott R Jones’s Open Call for his Cthulhusattva anthology. I knew next to nothing about Lovecraftian fiction written in the last two or three decades. Anyway, I read his book When The Stars Are Right: Towards An Authentic R’lyehian Spirituality, which suggested that he was interested in different approaches to Mythosian base concepts. So I wrote ‘Messages’, which he bought.

That encouraged me to believe that it might be possible to work with the roots of Lovecraftian ideas. But not too often. I’m not a great fan of mining the Mythos for mundane monsters, nor of Derlethian reworkings of the Mythos. All that Cthulhu versus The Baby Jesus, and ‘Guess which element I represent?’ doesn’t stand up well after a while. Use of Mythosian ‘gods’ and beings as monsters is fine if you enjoy that as a reader, but it eventually risks dragging them from the deeper point of it all, and they become just more godzillas. Or space godzillas.

Occasionally someone does still manage something clever, so I haven’t jammed the door completely shut. There are talented writers re-inventing things all the time – but at its worst, it’s tarted-up science fiction/horror without much originality. Cosmic horror itself – in the sense of a blind, uncaring cosmos and humanity’s sense of unimportance – is interesting, of course. I’m more curious about the relationship between humanity and that monstrous void than I am with who steps on who. And there’s only so many times your protagonists can go mad before someone starts looking at their watch…

Mind you, people pay you for it, which surprised me. Not that they’ll ever pay me again, not after saying the above…

sam: We both like Nyarlathotep the most. What is it about the Crawling Chaos that speaks to you?

john: Darn, my Mythosian weak spot. The great thing about Nyarlathotep is that he’s both unknowable and oddly knowable –he demonstrates intent at times, which gives you far more to play with. He intersects with and influences humanity in a way which other Mythosian figures do not. He may be mostly indifferent to this world, but he also toys with it. I get that.

sam: I’ll give you four favorites of mine. ‘Messages,’ ‘Where All is Night, And Starless,’ ‘Marjorie Learns to Fly,’ and ‘For She is Falling. I’ve read your author notes, cheeky as they are. ‘Messages’ and ‘Where All Is Night, And Starless’ are both Mythos stories, but the latter two are wholly original stories. What’s more, ‘For She is Falling,’ appeared in Vastarien. Tell me a bit more about these stories.

john: ‘Marjorie Learns to Fly’ has been oddly popular, though I don’t know why. It’s the story of a bored, underappreciated housewife (a totally deliberate old-style trope, yes), who finds herself being used – and doesn’t do quite what you might expect as a result. One of my more ‘English’ stories, probably. It reminds me of the humdrum suburban life of the seventies and eighties, the dull routine for so many people until something unusual intrudes. Marjorie is many real people. Maybe that’s the appeal?

‘For She is Falling’ is left open to anyone’s interpretation, and avoids giving certain identity to the protagonist. It’s potentially about mental ill health, and potentially about ecology, or about self-determination, or about the dwindling Hidden Folk. Or any and all of those. As I’ve said elsewhere, I don’t mind which people pick. It was very kind of Vastarien to publish that one, especially as I’m not a very good Ligottian.

sam: You once told me “For She is Falling” is an “optimistic story.” But…did I just read suicidal ideation into the story? Why is it “optimistic?”

john: I had the same problem with my story ‘Grey Dog’, which was variously called depressing, just weird, or very moving and positive. That one was simply intended as a portrait of how things were. I work from the inside out, which means that my characters develop through their own choices. The choice made at the end of ‘For She is Falling’ may be an ending in terms of a life, or it may be an escape into new life and freedom. As I said above, the protagonist’s very identity is left open. That lack of certainty was essential to me being able to feel the story myself, how it needed to end – on paper; further definition would have killed it. I can’t write things I can’t ‘feel’.

sam: I also like the final story, which is decidedly NOT optimistic. “At Vrysfontein, Where the Earthwolf Prowls” is very much the sort of story I like. You could remove the supernatural elements and still have a very real horror story about the Boer War and the origins of the practice of concentration camps. Why did you write this story?

john: My period-set tales are often versions of real events, and this one, for me, is an encapsulation of everything that went wrong for everyone, on all sides, during the Boer Wars – a tale without any nice frills or soothing options. And also a portrait of a man, Redvers Blake, who features in other stories of mine, a look at what makes us how we are. In his case, atheistic, weary and cynical, with little faith in anyone, especially the Empire for which he fights.

So it serves more than one purpose (if any of my tales can be said to have purpose). The supernatural allusions are only another symbol of the ghosts and fears that we pick up in life, that we carry with us. Blake is very real and down-to-earth, yet in his troubled humanity, I see him as closer to cosmic horror than many ‘Mythos’ figures.

sam: This is not the only story you write set in Africa. Coupled with ‘With the Dark and the Storm,’ you present stories that are very realistic about the looting of the continent. You portray colonizers who are obsessed with the concept of race, to the point where they shed any sort of pretence of “civilization.” Both stories recall Heart of Darkness not just due to the Africa setting, but because they are very critical looks at colonization. Is it difficult to write about these subjects? If so, why is it important to you?

john: Long answer. To start with, writing about Africa isn’t easy. For one thing, in a sense there’s no such place as Africa. There are disparate regions spread across a vast continent, isolated localities, areas of common language or religion, countries with artificial boundaries which were often created and enforced by colonialists – and so many more issues. I’m just finishing another ‘Africa’ weird story, concerning Amazigh (Berber) women in Morocco, and French colonialism. No connection to either of the stories you mentioned (although I have at least been to Morocco).

Along the same lines, it’s incredibly easy to get wrong unless you come from/have lived in the specific area or culture about which you’re writing. In general, I’d prefer African writers to do this stuff – I don’t plan to make it a habit. For the reprint in this collection, I quickly ran ‘With the Dark and the Storm’ by Nigerian writer and serious talent Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki (also a fellow author in the recent SLAY anthology). He didn’t explode, at least. You should check out his work.

I should add that one of the tropes which most annoys me (and there are many) is the ‘white saviour’ one. When I was nine or ten, it seemed exciting. As an adult, that constant reinforcement of “White guy connects with different culture, comes up with ideas they didn’t have or whatever, and then helps or saves them’’, grates terribly. It denies people from other cultures true agency. Nor is its use dead – you only have to look at the film Avatar. ‘With the Dark and Storm’ was originally written as a rebuff to some of those adventure tales.

Colonialism, though… one of the questions which interests me (and usually appals me) is what the process does to both sides. The fraying away of humanity, or the stripping away of it. Colonial powers don’t – or won’t – recognise that they themselves are changed by what they do. Both the United States and Imperial Britain, for example, were fuelled and formed through the blatant stealing and asset-stripping of other peoples’s lives and lands, and a treatment of those peoples which was at best duplicitous, at worst – so often – venal and murderous. There’s little point in feeling guilty as individuals – I’m not sure guilt on its own is a very useful emotion, anyway – but we must acknowledge what was done and seek to understand its impact. To consider what that makes our societies today. And it’s only proper that modern fiction should reflect those realities, if for no other reason than to counteract the bias, lies and obfuscation of generations of gung-ho pro-colonial literature. End of monologue.

sam: On social media, you often make Mr. Bubbles the horse seem like he’s very evil. Yet in ‘The Horse Road,’ he seems quite the noble steed. Tell me about this horse and his origins. Does he have a code of honor?

john: Haha. Gosh, I’ve never thought of Mr Bubbles as at all evil. What might come over is his casual dismissal of things which annoy him. He can be judgemental, and occasionally brutal. Maybe he’s that part of us which might remain when released from the ‘burden’ of most of society’s rules for getting along with each other. Politeness, favours, common courtesies, layers of obligation – he’s not very interested in those. His responses are visceral rather than intellectual (although he’s smarter than most suspect). And on the plus side, he’s a great egalitarian – he’ll kick almost anyone – and has no time for other people’s stupid prejudices.

As for the character, he and Sandra sprang fully-formed from childhood memories of pony books, Enid Blyton, and ‘chums’ stories. With a touch of folk horror and the occasional prod at H P Lovecraft. That traditional pony book bond is there between them, but not much of the day-to-day sentimentality. The bedrock is her unconditional love for him, and his utter loyalty to her. So his code revolves around those, and if he has nobility, they are the source. Had he not been born in her particular barn, maybe things wouldn’t have gone so well for anyone…

sam: What’s next? I know you have a mountain of editorial work left to do, but once you’re over that do you have any grand plans for a new work?

john: Editing… bah! We have three issues of Occult Detective Magazine to get out in succession with Dave Brzeski of Cathaven Press, then another volume of Sherlock Holmes & the Occult Detectives and The Book of Carnacki anthology for Belanger Books. Outside of and beyond those tasks, a lot of short stories to write.

Despite toying occasionally with the idea of another novel, I remain fairly wedded to the shorter form – novellas at most. My previous work has come out in many unconnected venues, some obscure, some better known, so I’m planning additional stories in the sub-genres where I already work, with the intent of putting out two, perhaps three or so further collections. These would gather the wayward kids, and add a substantial amount of new material.

Studies in Grey should gather together the more interesting or unusual of my Sherlock Holmes stories, including aspects and characters from my Last Edwardian cycle such as Mr Dry and Redvers Blake and the occasional scary/ab-natural element. Ain’t No Witch, if I do it, would be all the existing Mamma Lucy tales of a 1920s conjure-woman, plus new and unseen ones. Historical weird fiction or folk horror, I suppose you might call those.

More ambitiously, I’m working with a UK artist to see if a St Botolph collection (which would include some Mr Bubbles) is possible, and have been teased by a publisher about putting together a book of my gay weird fiction – another strand of mine. Plenty to do.

sam: Last question: is Yorkshire a real place? If so, how come I can’t find it on my map?

john: Yorkshire is a state of mind. And God’s own country, naturally.

sam: Thanks, John. I look forward to getting a physical copy of your book. It was an absolute pleasure to read.

john: Thank you as well. It’s been a draining imposition to be cross-questioned and interrogated in such a demanding manner, especially by a tall Texan, but at least you didn’t get my rank or serial number.

Where All is Night, and Starless, by John Linwood Grant, is due from Trepidatio on 7th July.

Sam L Edwards’ new collection Death of an Author is out on 25th June.

https://journalstone.com/bookstore/the-death-of-an-author/