Last time I was rattling on about some neglected writers of early ghost stories. We’d reached, rather oddly, Edgar Wallace and his questionable character Sanders of the River. You’ll have to bear with me whilst I navigate back to my actual subject here.

One thing I always liked about the Sanders stories is the coverage of complex local beliefs, especially those which centre round the evocatively-named deity or demon M’shimba M’shamba.

“M’shimba M’shamba was abroad, walking with his devastating feet through the forest, plucking up great trees by their roots and tossing them aside…”

Intrigued, I hunted for any more information on this West African God of Storms. The web was not helpful. One of the only references I could find was to M’shimba M’shamba of Houghton Hill. Sounds encouraging, doesn’t it? Perhaps a chilling tale of African power wreaking havoc in wherever Houghton Hill is (Cambridgeshire, apparently), only to be laid to rest by a brave young curate who has recently returned from a Mission in the Congo? Well, it’s even better than you think.

Yes, you guessed it. M’shimba M’shamba of Houghton Hill is, according to Google, someone’s pedigree Shetland Sheepdog, a little fawny-brown dog which yelps a lot. I had a sheltie just like it when I was little.

Not quite a real God, then.

The writer Henry S Whitehead was a real minister, though, as mentioned last time. Some of his Gerald Canevin stories include the value of having faith in the Christian God, but it isn’t a dominant theme. Two of my other favourite writers, William Hope Hodgson and H P Lovecraft, were less enthusiastic in their support for the established churches.

Lovecraft’s stories depicted the universe as a mostly empty void ruled by hostile or indifferent nightmares, with mankind at the mercy of the unknowable. And probably doomed. Nice. He described his own religious feelings in his correspondence:

“Personally, I am intensely moral and intensely irreligious… What the honest thinker wishes to know, has nothing to do with complex human conduct. He simply demands a scientific explanation of the things he sees. His only animus toward the church concerns its deliberate inculcation of demonstrable untruths in the community.” (Letters, 1918)

WHH, although the son of an Anglican minister, seems to have abandoned his father’s faith, or pushed it well to one side. His occult detective Carnacki was a scientist above all, although he at least thought there were benevolent forces which might occasionally intervene to protect the human soul. I don’t remember him packing crucifixes in his kitbag, and The Exorcist would probably have appalled him. No electric pentacle, for starters.

So we have to turn to the wonderful Mr Batchel, E G Swain’s creation, for good old fashioned vicar power. See, I did get there.

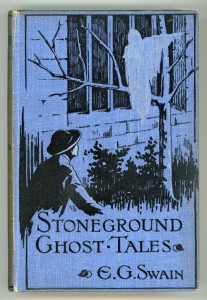

I don’t know how Mr Batchel drifted out of favour. E G Swain was a friend of M R James, and chaplain of King’s College, Cambridge. His short collection, Stoneground Ghost Tales, originally published in 1912, contains what might be described as utterly English ghost stories, gentle and redolent of place, of a long, slow sort of history rambling along its way.

If they fail to deliver the sense of incipient horror that marks some M R James stories, they succeed by providing the most genial of protagonists, a man who potters enthusiastically through life. James never pulled off this aspect in the same way. Mr Batchel himself is a treasure.

“Now Mr Batchel… was not much at home with young ladies, to whom he knew that, in the nature of things, he could be but imperfectly acceptable. With infinite good will towards them, and a genuine liking for their presence, he felt that he had but little to offer them in exchange.” (The Rockery)

He is mild without being characterless, personable in a way which can delight. He has an ongoing dispute over his shrubs with his gardener, and a love of odd objects which turn up in the soil. He believes in what I would call a very Church of England God – important and always around, but not given to crushing forests with His devastating feet.

There is a delicious, under-played humour in most of Swain’s work:

“But there are real ghosts sometimes, surely?” said Mr Batchel.

“No,” said the policeman, “me and my wife have both looked, and there’s no such thing.”

“Looked where?” enquired Mr Batchel.

“In the ‘Police Duty Catechism’. There’s lunatics, and deserters, and dead bodies, but no ghosts.” (The Richpins)

His tales are not ones of loathsome horror, or doom to come. They include hauntings, but avoid being trite or overly romanticised. They occur in a small fenland parish, and they are of loss, longing and wistful souls, and all the better for it. Incidentally, the story that most resembles M R James is The Man with the Roller, which really does feature a garden roller. It always makes me think of James’ The Mezzotint.

There were only nine of Swain’s Mr Batchel stories, although in the eighties David Rowland did a fine job extending the canon with a set of tasteful Mr Batchel follow-up stories. These are also well worth reading. They’re included in the old Equation Chillers collection of The Stoneground Ghost Tales, but you might be able to find some of them elsewhere.

And that, dear listener, is my other recommendation for the week. E G Swain.