In which we look at the pocket watch of Dr Watson’s late brother, Holme’s secret worries, the nature of the Science of Deduction, and the realm of the almost impossible – including the occult.

Let’s start with the obvious. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, Consulting Detective of 221b Baker Street, London, never knowingly encountered the occult, nor did he undertake any case in which he anticipated the solution to involve occult, psychic or other paranormal phenomena. He faced no genuine ghosts; he laid no malevolent spirits, and he had no encounters with demonic forces.

With that in mind, today we probe the question of Sherlock Holmes and the uncanny, the supernatural, or whatever you care to call it. And before anyone groans, we neither question the canon nor do we belittle less canonical interpretations. The original stories can stand proud, yet there is no doubt that variations on the theme interest a number of readers – and writers. So do bear with us…

As stated above, Conan Doyle made it clear in his stories that Holmes’s cases did not involve the psychic or supernatural. This might seem odd in some ways, given Conan Doyle’s personal belief in psychic matters, and the fact that spiritualism, mysticism and theosophy were common currency in late Victorian society. However, in the process the author did:

- ensure that the stories could be read by the widest possible audience;

- give himself a clear distance from the character he had created;

- replace one ‘magic’ with another – the preternatural deductive abilities of Holmes.

We tease with the word ‘magic’, because Holmes’s deductions are, at times, more accurate than should be possible. That Holmes should be correct so many times borders on the preternatural – and in some cases his approach is not deductive reasoning but inductive reasoning which ignores less probable options. For the purposes of the fictional narrative, he makes observations from which he comes to conclusions that are only likely to be valid – such as when he examines the watch of Watson’s late brother:

“Look at the thousands of scratches all round the hole—marks where the key has slipped. What sober man’s key could have scored those grooves? But you will never see a drunkard’s watch without them.”

The Sign of Four

In stating confidently that Watson’s brother had an alcohol problem, he does not consider the possibility that the man was extremely short-sighted, or that the brother or the father who owned the watch beforehand had a palsy which meant he could not easily get a key into a small hole. Such inductive reasoning, which occurs a number of times, means that Holmes need not be correct, but for him to be incorrect would not suit Conan Doyle’s purpose.

On a grander scale this leads to what has been called the Holmesian fallacy – a logical fallacy arising from the inability to absolutely rule out all other possible explanations. Which is relevant to the other meat of today’s piece….

The Ghost Elephant in the Room

Holmes’s stance on the world of the “supernaturalists” was a very particular one which is sometimes misinterpreted. Conan Doyle’s approach was rather clever in one sense – he used brief references to remove his consulting detective from the argument. Holmes did not say, as is often believed, that there was no such thing as the supernatural. He was occasionally dismissive of such things, yes, but there was a common theme to his few statements on the subject:

“If Dr. Mortimer’s surmise should be correct, and we are dealing with forces outside the ordinary laws of Nature, there is an end of our investigation. But we are bound to exhaust all other hypotheses before falling back upon this one.”

The Hound of the Baskervilles

And again, in another story of the original canon, ‘The Adventure of the Devil’s Foot’:

“It’s devilish, Mr. Holmes, devilish!” cried Mortimer Tregennis. “It is not of this world. Something has come into that room which has dashed the light of reason from their minds. What human contrivance could do that?”

“I fear,” said Holmes, “that if the matter is beyond humanity it is certainly beyond me. Yet we must exhaust all natural explanations before we fall back upon such a theory as this.

In essence, Holmes (when he was not just being sarcastic) was expressing the view that if such phenomena existed, then his logic, his ratiocination, were of neither value nor use. Psychic gifts and wandering wraiths were beyond the Science of Deduction. Conan Doyle has this echoed in another comment of Dr Mortimer’s:

“There is a realm in which the most acute and most experienced of detectives is helpless.”

In Holmes you have a man who prides himself on his gift of reasoning; if he were to be presented with situations where that gift could be of no use, where would that leave him? Such situations would challenge his very identity. Bluntly, it is not in the interests of the detective’s mental health even to acknowledge the occult.

“This Agency stands flat-footed upon the ground, and there it must remain. The world is big enough for us. No ghosts need apply.”

Sussex Vampire

“The world is big enough for us” – that is, there are more than enough conundrums and problems in everyday existence without delving into spiritual or mystic matters and potentially discovering more cans of worms – or a whole field of endeavour where he is of no use.

There is, however, a step that can be taken once Holmes’s statements have been processed. In using the phrase “forces outside the ordinary laws of Nature” and “beyond Humanity”, he raises interesting alternatives, even as he refuses to consider the matter as part of his own practice – or even existence.

The alternatives are that the paranormal might have its own rules, its own principles, ones to which men such as Holmes are not privy, or that it might operate without rules, where effect precedes cause, where there is no rational set of sequences or motives, and evidence is mutable or utterly unreliable. A terrifying thought to Holmes, who lived by earth-bound logic.

As the intrusion of the paranormal must have its effect upon the normal to be observed at all, a genuine occult mystery therefore suggests that two different approaches might be needed at once – the ‘logic’ of the normal, and the ‘logic’ of the paranormal. Any truly successful occult detective must surely have to marry both of these in order to succeed. They must be at least a half-Holmes.

The Science of Deduction

Logic has been described as reasoning conducted or assessed according to strict principles of validity, and that process of reasoning in which a conclusion follows necessarily from the premises presented, so that the conclusion cannot be false if the premises are true. The Science of Deduction is seen as the process of observation, hypothesis, prediction, experimentation and conclusion.

From this, we can see that both Sherlock Holmes and a skilled occult detective can apply the science of deduction to cases.

CASE A: Let us suppose that Holmes observes a mist-like human figure arise within an ancient manor house’s oak-lined dining room. He hypothesizes that this is due either to natural causes such as gas released from underground pockets, or a man-made phenomenon, utilising lanterns and mirrors. He draws on his initial observations and knowledge of the sciences to predict that evidence will be found of one of these, and experiments by altering the conditions, observing under different circumstances, or taking samples, etc. He gathers further background evidence, adds in his knowledge of human behaviour, and concludes that a brother and sister have sought to fool their dying uncle into making a new will.

CASE B: Now let us suppose that an occult detective comes across a similar initial situation. She hypothesizes much as does Holmes. She predicts and experiments, but finds neither original hypothesis holds up. Therefore she forms another hypothesis, that this is an ab-natural phenomenon with a quite different source. She draws on her initial observations, and on knowledge of the ab-natural, to predict that a particular type of presence has taken up residence there. She then experiments with wards and remedies against specific entities, takes samples and so forth. She gathers further background evidence, adds in her knowledge of human behaviour, and concludes that there is a genuine non-corporeal entity which seeks vengeance on the brother and sister for their involvement in a murder.

The difference is not in the process of reasoning, but in the underlying premise. If Holmes starts from the premise that the supernatural or ab-natural cannot and does not exist – that it is ‘impossible’ – he must pursue the mundane route, however complicated or potentially fruitless. The occult detective, on the other hand starts with the premise that the supernatural may exist, and therefore has two routes open to her.

In theory, Holmes could choose to do the same, but in canonical terms, he would lack any orderly body of knowledge about these improbable possibilities. He would have no card index, Burke’s Peerage, Bradshaw or network of contacts and informants which might offer useful clues as to which lines to pursue. Therefore, even if he could embrace a “supernaturalist” philosophy, he would need to amass an entirely new body of knowledge.

The Detectives in the Shadows

We can see various interpretations of the ‘occult Holmes’ option in three fictional characters who were contemporaneous with the Great Detective’s adventures – Thomas Carnacki, Dr John Silence, and Flaxman Low. Readers in the Edwardian era could have easily picked up stories by Conan Doyle and by the creators of each of these occult detectives.

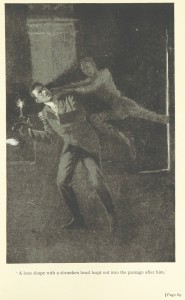

We often describe Thomas Carnacki, created by William Hope Hodgson, as the first true occult detective, and also as the only one who is likely to have appealed to the canonical Holmes. Carnacki was no psychic, and would therefore not be ‘tainted’ in Holmes’s eyes by pretensions of mystic gifts. There were ab-natural phenomena and presences, in Carnacki’s view, but many supposed manifestations were perfectly natural in origin, and were explainable as based on either ignorance or deceit. He utilised scientific method in order to exclude these deceits before he accepted the possibility of a genuine supernatural event. In practice, Carnacki tended towards the tools of the mundane detective – cameras, hairs used as motion sensors, scientific apparatus etc. – rather than taking Holmes’s more intellectual approach.

(For more on the enduring appeal of Carnacki the Ghost Finder, see here: carnacki-the second great detective)

Dr John Silence, on the other hand, created by Algernon Blackwood, was a man of psychology and mysticism, employing spiritual insights and gifts to probe unusual situations. His was a world of ascetic pursuits and moral clarity, with a touch of Holmes’s distance from the ‘common man’ and more of the intellectual standing. He favoured the mental struggle with dark forces, rather than carting around a load of paraphernalia. Silence’s mind at least would have caught Holmes’s attention, but Holmes may well have dismissed Silence’s psychic abilities.

And then there was Flaxman Low, created by E & H Heron – the joker in the pack. If Holmes might occasionally have approved of Low’s penchant for direct action rather than psychic flim-flam, he would have put his head in his hands at the distinct lack of logic in either Low’s cases or his actions. Low comes to conclusions before gathering sufficient evidence, and blasts away at whatever foes he perceives. If Holmes says, as he does in ‘The Sussex Vampire’,

“What have we to do with walking corpses who can only be held in their grave by stakes driven through their hearts? It’s pure lunacy.”

then Flaxman Low surely replies: “Worry not, Holmes. I’ve already shot the walking corpses and am about to set fire to them.”

For devotees of the canon, Low would, we suspect, be the least appealing of the trio.

(We look deeper into the bizarre world of Flaxman Low here: flaxman low triumphant)

In a forthcoming anthology Sherlock Holmes and the Occult Detectives (edited by old greydog and coming from Belanger Books in 2020), we hope to demonstrate the many ways in which Holmes’s logic and the occult investigators’ willingness to embrace another set of rules entirely might work alongside each other. In the process, we hope to portray how Holmes and Watson might choose to adjust to – or reject – the presence of “forces outside the ordinary laws of Nature”.

Holmes shrugged his shoulders. “I have hitherto confined my investigations to this world,” said he. “In a modest way I have combated evil, but to take on the Father of Evil himself would, perhaps, be too ambitious a task.”

The Hounds of the Baskervilles

For musings on other matters related to 221b, we also recommend an extensive and fascinating recent post by noted Sherlockian writer and editor David Marcum, in which he covers the role of numbers, and the range of untold cases mentioned in the canon (amongst other things):

And for those who openly embrace the occult detective concept, Occult Detective Magazine #6 should be out before the end of the year.