We’ve all been there. You decide to sail round a few continents in the worst storms imaginable, make a pact with the Devil and then, dash it, you’re doomed to wander the Seven Seas for eternity. So here’s everything you didn’t want to know about the most haunted ship ever. The origins of the story, Gothic fiction and the death of Napoleon in Part One today. In Part Two later this weekend, Chilean mythology through to Roger Zelazny, calling in at James Mason, Uncle Scrooge McDuck and Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea along the way.

Put out the galley fire and swallow that grog, it’s Stranger Seas Eight…

(This first part’s the semi-literary and historical bit, by the way. We’ve even quoted sections of the relevant works, in order to prove we don’t make everything up.)

Der Fliegende Hollander, De Vliegende Hollander. Over three centuries, the legend of the Flying Dutchman has mutated many times. Usually the Dutchman is the ship itself; sometimes the Dutchman is its captain, cursed to be the equivalent of the Wandering Jew.

It all began in the 17th century – we think. The legend was certainly established by the middle of the 18th century, but we’ll never know the exact details. There are two named candidates for the origin of the story, a Dutch explorer called Van der Decken and a man called Barend or Bernard Fokke. Both were sea-captains who were supposed to have worked for the Dutch East India Company, and made extensive voyages around 1650 – 1680.

Not a lot is known of Captain Van Der Decken, aka Cornelius Vanderdecken. The tale is that his ship got caught up in a storm around the Cape of Good Hope (South Africa), and he swore that he would finish the voyage even if it took him until Judgement Day. It was said that because of the vow that he was forced to sail the seas forever by the Devil.

Captain Barend Fokke was certainly genuine. A Frisian born sailor, he was renowned for fast voyages between Java and Holland (then the Dutch Republic). In 1678 he is supposed to have covered the distance in just over 3 months. This was pretty impressive, and gave rise to talk that he was in league with dark powers, possibly the Devil himself.

By the late 18th century, the legend was pretty well established. A doomed captain/ship and crew would appear to other ships, either dark and ruined or haloed with a ghostly light, and often during a storm. Sometimes the sight presaged evil to come, sometimes it was just one of those things put there to remind you that you needed to go to confession again fairly soon.

We’ll get slightly literary. A pickpocket called George Barrington was sentenced to transportation to Australia in 1790, travelling there between March and September 1791. Barrington supposedly wrote about that journey in A Voyage to Botany Bay (1795). We say supposedly because it seems likely that whatever he produced was altered or re-written for publication. In the published book, the passage goes:

I had often heard of the superstition of sailors respecting apparitions and doom, but had never given much credit to the report; it seems that some years since a Dutch man-of-war was lost off the Cape of Good Hope, and every soul on board perished; her consort weathered the gale, and arrived soon after at the Cape. Having refitted, and returning to Europe, they were assailed by a violent tempest nearly in the same latitude. In the night watch some of the people saw, or imagined they saw, a vessel standing for them under a press of sail, as though she would run them down: one in particular affirmed it was the ship that had foundered in the former gale, and that it must certainly be her, or the apparition of her; but on its clearing up, the object, a dark thick cloud, disappeared.

Nothing could do away the idea of this phenomenon on the minds of the sailors; and, on their relating the circumstances when they arrived in port, the story spread like wild-fire, and the supposed phantom was called the Flying Dutchman. From the Dutch the English seamen got the infatuation, and there are very few Indiamen, but what has some one on board, who pretends to have seen the apparition.

Not long after, at the start of the next century, Thomas ‘Anacreon’ Moore wrote a poem about the ghost ship legend which is worth quoting in its entirety – a) it’s creepy, and b) we don’t do much versifying here.

ON PASSING DEADMAN’S ISLAND, IN THE GULF OF ST. LAWRENCE, LATE IN THE EVENING, SEPTEMBER, 1804.

See you, beneath yon cloud so dark,

Fast gliding along a gloomy bark?

Her sails are full,–though the wind is still,

And there blows not a breath her sails to fill!

Say, what doth that vessel of darkness bear?

The silent calm of the grave is there,

Save now and again a death-knell rung,

And the flap of the sails with night-fog hung.

There lieth a wreck on the dismal shore

Of cold and pitiless Labrador;

Where, under the moon, upon mounts of frost,

Full many a mariner’s bones are tost.

Yon shadowy bark hath been to that wreck,

And the dim blue fire, that lights her deck,

Doth play on as pale and livid a crew,

As ever yet drank the churchyard dew.

To Deadman’s Isle, in the eye of the blast,

To Deadman’s Isle, she speeds her fast;

By skeleton shapes her sails are furled,

And the hand that steers is not of this world!

Oh! hurry thee on-oh! hurry thee on,

Thou terrible bark, ere the night be gone,

Nor let morning look on so foul a sight

As would blanch for ever her rosy light!

Our chum Anacreon notes: “This is one of the Magdalen Islands, and, singularly enough, is the property of Sir Isaac Coffin. The above lines were suggested by a superstition very common among sailors, who called this ghost-ship, I think, The Flying Dutchman.”

Blackwood’s Edinburgh magazine published a Flying Dutchman tale in 1821 called Vanderdecken’s Message Home, which included the belief that crew of the Dutchmen would seek to send letters to loved ones, even though the recipients would be long dead.

Soon a vivid flash of lightning shewed the waves tumbling around us, and in the distance, the Flying Dutchman scudding furiously before the wind, under a press of canvas…. One of the men cried aloud, “There she goes, top-gallants and all.”

The point being that they were in the middle of a storm, and no normal ship would be able to bear top-gallant sails under such conditions without disaster.

In 1833 (we’re being semi-chronological, don’t mock) Edgar Allen Poe wrote MS. Found in a Bottle. Although this is possibly a satire of sea tales, it includes an excellent encounter with what may well be the Dutchman:

Casting my eyes upwards, I beheld a spectacle which froze the current of my blood. At a terrific height directly above us, and upon the very verge of the precipitous descent, hovered a gigantic ship of nearly four thousand tons. Although upreared upon the summit of a wave of more than a hundred times her own altitude, her apparent size still exceeded that of any ship of the line or East Indiaman in existence.

Her huge hull was of a deep dingy black, unrelieved by any of the customary carvings of a ship. A single row of brass cannon protruded from her open ports, and dashed off from their polished surfaces the fires of innumerable battle-lanterns, which swung to and fro about her rigging. But what mainly inspired us with horror and astonishment, was that she bore up under a press of sail in the very teeth of that supernatural sea, and of that ungovernable hurricane.

Poe later adds:

The ship and all in it are imbued with the spirit of Eld. The crew glide to and fro like the ghosts of buried centuries, their eyes have an eager and uneasy meaning, and when their figures fall athwart my path in the wild glare of the battle-lanterns, I feel as I have never felt before…

Our next reference is to The Phantom Ship (1839), written by Frederick Marryat, the author of Mr Midshipman Easy and other books. Marryat served with distinction during the Napoleonic Wars as midshipman and eventually captain in the Royal Navy. The Phantom Ship is not without flaws – in fact it’s a tad boring in parts – but some people will know the chapter The White Wolf of the Hartz Mountains, which has been anthologised a lot.

The book is basically about the Flying Dutchman legend. Philip Vanderdecken (remember that surname?) seeks to save his father, who has been doomed to sail for eternity as the Captain of the Bewitched Phantom Ship, after he made a rash oath to heaven and slew one of the crew whilst attempting to sail round the Cape of Good Hope. Vanderdecken discovers that there is a way by which his father may be laid to rest, and vows to live at sea until he has achieved this. This is dear papa’s revelation to his wife early on:

“‘Alas! no—be not alarmed, but listen? for my time is short. I have not lost my vessel, Catherine, but I have lost!—Make no reply, but listen; I am not dead, nor yet am I alive. I hover between this world and the world of spirits. Mark me.’

‘For nine weeks did I try to force my passage against the elements round the stormy Cape, but without success; and I swore terribly. For nine weeks more did I carry sail against the adverse winds and currents, and yet could gain no ground and then I blasphemed,—ay, terribly blasphemed. Yet still I persevered. The crew, worn out with long fatigue, would have had me return to the Table Bay; but I refused; nay, more, I became a murderer—unintentionally, it is true, but still a murderer. The pilot opposed me, and persuaded the men to bind me, and in the excess of my fury, when he took me by the collar, I struck at him; he reeled; and, with the sudden lurch of the vessel, he fell overboard, and sank. Even this fearful death did not restrain me; and I swore by the fragment of the Holy Cross, preserved in that relic now hanging round your neck, that I would gain my point in defiance of storm and seas, of lightning, of heaven, or of hell, even if I should beat about until the Day of Judgment.’

‘My oath was registered in thunder, and in streams of sulphurous fire. The hurricane burst upon the ship, the canvass flew away in ribbons; mountains of seas swept over us, and in the centre of a deep o’erhanging cloud, which shrouded all in utter darkness, were written in letters of livid flame, these words—Until the Day of Judgement.’

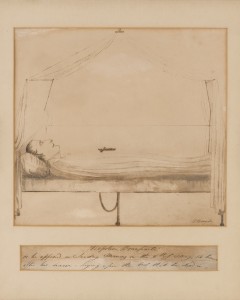

Marryat also had the odd distinction of sketching the corpse of Napoleon Bonaparte on St Helena, when he was charged with bringing back to England the despatches announcing Napoleon’s death. He wasn’t a great artist, but here it is, a sliver of history:

Finally for this part, we’ll mention but dash fairly rapidly past Richard Wagner’s opera Der Fliegende Hollander from 1843, because we find it somewhat dull at times. There are clear echoes of the Wandering Jew again, as the plot line was adapted from a story by Heinrich Heine in which the Dutchman is referred to as ‘the Wandering Jew of the ocean’.

Lots of people do like Wagner, of course, and so you can listen to the overture here:

Do join us for Part Two in a day or so, when we follow the tangled threads of the Dutchman into the twentieth century…

When I was a kid, the first time I heard the phrase “Flying Dutchman”…. let’s just say there’s still a cartoon in my head of a man with wings….