“The contamination of the water of the Thames by the sewage of London, which here falls into the stream on both sides, by the refuse of gas works and chemical factories, had, probably, much to do with the rapid decomposition of the bodies. In consequence of the danger to the health of the community it was found absolutely necessary to inter many of the bodies before they could be claimed by their friends.”

The Wreck of the Princess Alice (Edwin Guest, 1878)

In 1966, Ewan MacColl wrote ‘Sweet Thames Flow Softly’, a haunting and romantic folk song which we first encountered in a recording by Planxty (Planxty, 1973).

“Swift the Thames runs to the sea, flow sweet river flow.”

Yet a century earlier, the Thames was not considered so sweet, as we have mentioned in earlier posts. Try this cartoon, for example:

“Father Thames Introducing His Offspring to the Fair City of London. (A Design for a Fresco in the New Houses of Parliament.)” engraving by John Leech. Punch magazine, July, 1858

“Father Thames Introducing His Offspring to the Fair City of London. (A Design for a Fresco in the New Houses of Parliament.)” engraving by John Leech. Punch magazine, July, 1858

Twenty years after the above cartoon was drawn, on 3 September 1878, the Princess Alice pleasure steamer was in a catastrophic collision with the colliery boat Bywell Castle, a collision which resulted in the loss of up to 700 lives.

Edwin Guest’s contemporary account, quoted at the start of this piece, listed the names of those whose death was confirmed, but others were lost, some unnamed, to the sludgy waters. In the period which followed, attempts were made to ship effluent from the area, and to purify at least some of the sewage discharge. But the Thames remained more polluted than sweet for many years…

It is in such a grim spirit, that we return to our serialisation of Alan M Clark‘s illustrated novella Mudlarks and the Silent Highwayman…

MUDLARKS AND THE SILENT HIGHWAYMAN

SEGMENT 9

Surprised that he had not hurt himself, Albert rose awkwardly. His feet, still in his shoes, sank deep into mud. That didn’t seem right. But then he remembered that Hardly had been in pursuit. Albert tried to look back that way he’d come, and found he couldn’t change the angle of his vision.

His muddied head wouldn’t move! His right cheek and ear rested on his shoulder. Everything appeared sideways.

Albert turned his body—the only way to realign his vision—glancing around quickly.

The pier—gone!

Something happened…I don’t remember…

Had he fallen in the water and been carried downstream?

He kept trying to move his head, looking out for danger.

Nothing there, or, at least, very little. Everything, including the sky, had taken on a similar shade of gray. A near featureless foreshore extended into the dreary distance to either side and behind him.

Why can’t I move my head? Have I broken my neck?

He reached up to feel with his hands.

Yes—he felt bones pushing the muscle and skin of his neck outward. Yet he felt no pain.

That fall should have killed me!

He felt fortunate to have survived, and thought of another incident in his life in which luck had safeguarded him. A draft horse had kicked him in the head while Albert reached for a farthing that had got away from him and rolled off the kerb to lie beneath a wagon. The force of the blow had tossed him at least ten feet onto the flagstone footway, but he had walked away with only a gash on his forehead.

Albert would have to be careful not to make his neck worse before he could mend up. He might need a surgeon’s help.

An odd quiet suggested his hearing had somehow suffered from the fall. Snapping his fingers, told him that wasn’t so. What had happened to the rumbling hubbub of the city surrounding the river, the sounds of countless feet, hooves, and wheels upon the stones of the roads, the innumerable voices of the inhabitants, the ringing grind and clank of industry, and commerce on land and in the river?

The disorienting sideways view became tolerable in short order. He saw clearly the chill, gray river, its slow current lapping at the colorless mud along the edge. The bank had a different shape from what he’d expect to see near the West India Docks Pier, it’s curve more gentle. With the morning sun low in the eastern sky behind the embankment at his back, he should see its light shining upon the buildings across the moving water to the west. Instead, he saw merely dim silhouettes of the landscape; a couple of rocky prominences, a couple of dead trees, and no more. He saw no river traffic.

Yes, taken downstream. Just don’t remember.

Albert turned to his right and began walking upstream.

In the distance, he saw a figure, a scavenger perhaps. Abandoning his natural caution, Albert ran toward the figure, but his vision, bouncing with his head on his shoulder, became too disorienting. Slowing, he got a good look. A boy, it seemed, crouched on the foreshore, poking at the mud with a stick. He wore several layers of mud-caked clothing, mostly rags, and some sort of large, cumbersome hat upon his head. No—not a hat, but a mass of filth-clotted, tangled hair, also caked, as if he, too, had fallen head-first in the mud. The figure seemed a growth on the gray landscape. Displaying no curiosity, let alone wariness—something unusual in a scavenger—the child didn’t look up as Albert approached.

“Tell me, please,” Albert said, “where are we on the river?”

Like an old man, bent and broken with age, the boy rose slowly. For all his filth, he had a gold watch chain fixed to one of his numerous waistcoats, the end disappearing into pocket, where, presumably, a watch rested. So, indeed a scavenger, and a successful one too.

Finally, he lifted his head.

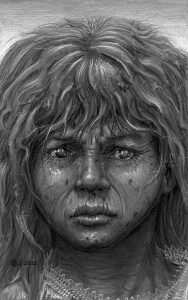

Albert gasped to see the features beneath the rat’s nest of hair. Yes, a child—the rounded shape of the face told that—though wrinkled with untold years of wear on what otherwise had a boyish shape. The lips and nostrils suffered cracks at the edges. The eyes, dull and somehow vacant, held the smallest hint of a great yearning deep inside. Indeed, Albert could see in the silent pleading gaze a curious and inquisitive boy, a poor waif trapped within an ancient, slow-moving body.

Revulsion drove Albert back a few stumbling steps. He felt the tingling of his skin tightening into gooseflesh.

The ancient boy dropped the stick, raised his hands toward Albert. The fingernails were several inches long, curled in upon themselves, some raggedly broken.

Albert turned and ran despite the disorienting effect of his bouncing vision.

MUDLARKS AND THE SILENT HIGHWAYMAN

SEGMENT 10

The grayness seemed to absorb Albert. His mind having nothing visual to grab onto, he lost all sense of direction and feared that he might make a circle, running into the boy again. Albert stopped and turned, saw the boy not too far away. He’d picked up his stick, gone back to poking at the mud, and didn’t appear to be a threat.

A muffled cry of, “My eye!” seemed to come from the mud beneath his stick.

“My apologies,” the boy said in a thin, cracked voice.

Did I awaken or is this still dream?

Albert looked closely at the back of his right hand, saw a smear of soil caught in the tiny hairs, the grit trapped beneath his nails, and a bit of dried grass caught in a sharp split of his thumbnail. He pressed that nail hard into his index finger until he felt pain.

No, not dreaming.

A tap on his left shoulder, and he spun around.

George Hardly!

Albert stumbled back and fell on his arse, scramble backwards on all fours to get away. Hardly followed.

Albert could see only the boys torn breeches and feet, the shoe missing from the left foot. He turned onto his left side to see more of him.

Hardly held his hands out to his sides. His scarred face, wide eyes, and trembling lips had a pleading look.

Even so, Albert covered his head with his arms for protection, drew his knees to his chest.

“I mean no harm,” Hardly said, his voice tremulous.

Albert peeked up a him from between fingers. The older boy appeared on the verge of tears. Hardly reached out a hand. Though reluctant, Albert finally took it and stood with assistance. The two boys looked at one another.

Hardly’s shirt was bloodied and had a hole in it on the left side of his chest. “He had a bigger knife,” he said with a grimace. “I fell down the bank, got lost. I recognize you, but nothing else.” He grimaced again. “What happened to your head?”

“I fell on it.” Albert backed away. “Leave me be.”

“I know… I-I harmed you,” Hardly said. “I don’t expect you’ll forgive, but I need to find my brothers. This wants help.” He gestured toward the hole in his chest, looking fearful. “Your head wants help too.”

Albert continued shuffling backwards. Hardly kept up, walking slowly.

“Stay away,” Albert said, and the other boy slowed, following from a distance.

MUDLARKS AND THE SILENT HIGHWAYMAN

SEGMENT 11

Albert saw the figure of a young girl ahead, another filthy waif in rags, not quite so bent with age as the ancient boy he’d seen earlier. She’d lost most of her right arm. A withered nub, hung out of her gray, rotting shift. Moving toward the girl, Albert watched her poke at something in the mud with a stick held in her remaining hand. “Just a rock,” she said, presumably to herself. She spoke slowly, as if the effort was practiced, not natural. “No life, no memories.”

He stopped to speak to her. Hardly became still about fifty feet away.

“Can you tell me where I am?” Albert asked.

She looked him in the eye. Although appearing sad and withdrawn, her gaze didn’t frighten. She had crow’s feet at the corners of her eyes, creases around her mouth, much like those of Albert’s mother. Her skin had the liver spots of someone much older still.

“Sticks,” she said, simply.

He looked at the stick in her hand.

“What did she say?” Hardly asked.

Albert waved the older boy’s words away. “Do you live hereabouts?” he asked the girl.

Her eyes widened briefly at the word, “live.” The crow’s feet disappeared. For a moment, she looked like any little girl. She seemed to search his face for meaning.

Albert became uncomfortable, trapped within her gaze.

Then a look of fright fixed her features. The crow’s feet returned. “The woolen mill, that’s where I…” Her voice trailed off for a moment. “The machine was so thirsty, never got enough of the oil, never satisfied. Had a hunger too…” She left the stick upright in the mud and rubbed the nub of her right arm. “…and a mean bite.”

Finally the girl frowned and her gaze shifted. She shrugged, and took up her stick. “You’ve only just come, you and your friend,” she said, turning away and poking the mud. “You know nothing.”

Hardly had approached. “Do you live here?” he asked the girl.

“No live,” she said, “no die. No coins. One hundred years before I can go without paying the fare. Maybe tomorrow—don’t know how long I’ve been here. Not as long as he has been.” She gestured toward the boy Albert had first approached, now a mere thirty yards away.

The air having cleared slightly, Albert saw several other children wandering the river’s edge in the hazy distance. Their movements slow and unnatural for children, he assumed they all suffered the same condition, whatever that was.

“Which way to Limehouse?” Hardly said. He grabbed the girl by the shoulders. The nub of her right arm broke off in his grip. He threw it to the ground as if it had stung him, and looked at the girl, his mouth gaping in horror. She made no complaint, nor any expression of pain or surprise.

Hardly’s astonishment emerged as a great whooping sound. Then he was in a rapid stumble to get away. He disappeared into the grayness.

Albert, transfixed by the drama, stood dumbly wondering how he might help the girl. “Are you…?” he began.

The girl looked briefly at the nub of her arm on the foreshore before turning away toward the river.

Is she so ill she cannot feel? Has he made them all sick?

Albert hadn’t wanted to believe Thomas’s tale of the Silent Highwayman, but now he easily accepted that the skeletal phantom existed.

He’s done this, and now…

“Luck is with you,” the girl said, pointing out over the water. “He comes for you.”

Albert saw a small boat, much like his wherry. From its stem, a green lantern swung, sending out a sickly light that infected nearby mists. A gaunt cloaked figure stood at the tiller. The water appeared unusually troubled beneath the boat.

A panic in Albert’s chest shifted to his throat, raising his head upright, and he ran, the muddy foreshore sucking on his every step.

to be continued…

You can also see the full story of mudlarks on the Thames unfolding daily here:

https://ifdpublishing.com/blog/f/mudlarks-and-the-silent-highwayman

The Mudlarks book itself, illustrated throughout by Alan, is available now on Amazon, and directly from the publisher through the links below: