Yes, today we conclude our serialisation of Alan M Clark‘s moving and lavishly illustrated novella Mudlarks and the Silent Highwayman, set by the polluted River Thames of the nineteenth century…

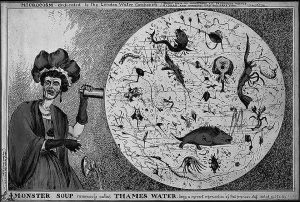

“Monster Soup commonly called Thames Water” Coloured etching by W. Heath, 1828

“Monster Soup commonly called Thames Water” Coloured etching by W. Heath, 1828

MUDLARKS AND THE SILENT HIGHWAYMAN

SEGMENT 12

Albert made it to firmer ground, picked up speed, only to stumble on something in his path. Falling, he rolled and lifted himself quickly to his feet.

Albert saw what had tripped him—Papa’s winning smile, half-submerged in the muck. Mud had oozed into the open mouth, slid in a smear across the uneven teeth, but Albert would recognize that grin anywhere.

He reached—he had to help if his father were somehow trapped alive under the mud.

Upon touching his father’s lips, he knew his mother’s feelings for the man, their history together.

She’d become pregnant while unwed. Her family, too poor to feed another hungry child, turned her out in the street. Mum had a meager income working as a cardroomer at a fearnought mill. She could barely afford lodgings of her own. Soon to be a mother needing an income more than ever, she’d fallen under the thumb of the mill’s overlooker, a cruel man named Ganloff.

Papa competed for fares at the Kidney Stairs in Limehouse, very near the fearnought mill. At midday, he’d take a break, purchase food from a street vendor, and have a stroll while eating. On one of those walks, he found Mum in the alley that ran beside the fearnought mill, hiding behind a stack of crates, her hands covering her face.

“Come, share my bread and cheese,” he’d said. “You appear to be eating for two, though you’re very thin.”

He coaxed her out of her hiding place, took care to gain her trust, and asked for her story.

“I’m too ashamed to tell it,” she said, her red-rimmed eyes downcast.

Papa gave her a gentle smile, said, “There’s nothing that unburdens one so much as telling the worst to a willing stranger. Should you trust me, whatever it is, I shan’t think the less of you for it.”

She did not confide in him on that day.

With his smile and good humor, he lifted her heart and she laughed many times during their first meal together. They met in the alley at midday many times over the following month.

One day, she placed her hands on her swollen belly and said, “When the father found out I were knapped, he left me and went to sea. Mr. Ganloff found out, said should I want to keep my position, I’d please him and his three brothers. All are scurfs here at the mill. No one disobeys them. Some of the women they command are pimped on the street. Once the baby comes, that’s where they’ll send me.”

Papa courted Mum briefly. Already friends, true affection drew them even closer. He asked for Mum’s hand. She quit the mill and married him before young Albert was born. Mum had asked Albert Gladwick senior if she could give his name to her boy.

He loved me and raised me as his own.

He saved Mum from the street! No wonder she’d forgive him anything.

Along with the revelations of Mum’s past came the understanding that she had died in the night. Passing on, she’d dropped his father’s smile on the foreshore. Though the flesh felt real, somehow Albert knew the grin to be mere memory.

Distracted by the experience, consumed by his feelings of loss, Albert had forgot briefly about the one approaching in the boat. Sudden realization of the need to flee forced a gulping breath that brought back the panic.

He wiped away his tears, looked out over the water, and saw that the Silent Highwayman had drawn closer, not a hundred yards away.

Albert got up ran again. Deeper mud confounded his steps and sucked away his energy. Still, he plodded on, moving away from the water. Periodically looking back, he saw that the river remained beside him—he could not put distance between himself and the water, nor between himself and the one in the boat.

MUDLARKS AND THE SILENT HIGHWAYMAN

SEGMENT 13

So concerned with what lay behind him, not watching his step, Albert tripped on another object in the mud. His foot had hooked onto something that he now dragged behind him. Turning, he saw he’d pulled what looked like a toy steamship out of the mud. The wet, clay-like soil flowed away from the thing, revealing a motionless burst of fire from a cannon, and equally still black coal smoke above the ship’s funnel. About the size of the bucket in which he’d carried water the day before, the small vessel, with its intricate rigging and perfectly formed, unmoving crew on deck, appeared as vividly complex as any ship he’d ever seen. Its tiny signal flags, though motionless, lifted on an unfelt breeze. Even the smell of it, the coal smoke and a familiar fermentation of aging in the sea, mixed with what he believed to be the odor of spent smokeless powder, confirmed that it was no toy.

Albert reached to touch an explosive shell, suspended just ahead of the still and silent flash at a cannon muzzle.

Instantly, he knew his father’s horror at finding the dead and dying in Alexandria following the British fleet’s three-day-long bombardment of the city. Papa had been among the sailors sent from the fleet to fight alongside the British Expeditionary Force in the battle of Kafr El Dawwar. He’d been wounded and suffered the amputation of his leg, then was left in the heat of a dust and fly ridden field hospital to recover with little to help relieve his pain. Albert knew the sights of mutilation, the sounds of agony, the stench of blood that had become lodged in Papa’s mind from his time in the Anglo-Egyptian War.

Having refused to fire upon young boys conscripted by the Egyptian forces to fight against the British, Papa had been the subject of a court-martial. With consideration for the loss of his limb, his sentence was merely the loss of his pension. Much worse, he’d lost his pride.

Compassion for Albert Gladwick senior welled up in young Albert’s heart. Regretting his harsh judgement of the man, he knew again his love for his father.

The ship was a memory of the one Papa had served aboard during the war. He had dropped the small vessel on the muddy foreshore when he’d passed on.

Yes, both his parents had passed away. But away where—where had Papa and Mum gone?

The girl’s voice, very close, startled Albert, and he swung around to face her. She had followed, come up from behind, and crouched down beside him in the mud.

“You found a memory,” she said, a small delight in her voice, a shade of it in her eyes. “If you want to keep it, you’ll have to carry it with you. Looks like a weighty one. May I touch it?”

Albert nodded uncertainly. She reached for one of the tiny ship’s flags, and closed her eyes. Her features moved subtly with emotion. Moisture appeared among her dry lashes.

“Alice,” she said, as if remembering. “That was my name. Born 1832. I shan’t have thought of that without touching the soldier’s memory.” Her voice had gained more life.

Was her name? Questions arose that Albert found too frightening to ask. No, she’s daft or touched.

“Who are they?” he asked uneasily, gesturing toward the waifs wandering the foreshore in the distance.

“We are orphans and paupers’ children, mostly. Paupers who arrive grown have little hope if they are here for very long. With time, the heaviness of their hearts weighs them down. They sink deep into the mud and are lost until their time of remembrance is done.

Albert looked down at the mud. As he’d done when finding his father’s smile, he pictured the horror of an adult buried beneath him. “How many?” he asked.

“Some arrive each day. Those of us unable to pay to cross over must wait one hundred years.”

With his gasp of astonishment, Alice placed her remaining hand, a reassuring one, upon Albert’s arm. “You’ll not suffer as we do,” she said with a touch of envy. Wiping away her gathering tears, she turned toward the water and gestured. “He’s here for you.”

The cloaked figure in the boat had landed a few yards away.

Albert recoiled, leaning into the small ship’s rigging.

The figure made no move toward him, simply held out a hand in greeting, or perhaps to help Albert board the small boat. Silent, yes, but not a highwayman. Albert saw no menace in the pale face beneath the heavy hood.

“There’s nothing to fear,” Alice said.

She’s trapped here, yet she has it in her heart to comfort me?

“You have someone waiting on the other side,” she said, not quite asking. “He wouldn’t have come if you couldn’t pay the fare.”

The ferryman, as Papa said! Albert laughed at himself, and the fear Thomas Conway had given him of the Silent Highwayman. He is not here to rob health, but to carry people across.

Did he take Papa and Mum? If so, they must have somehow paid the fare.

He saw that the landscape across the river had taken on more color. The sky above reflected something like flowing cloth made of light, so much like the glimpse of the northern lights he and Papa had got from the church tower.

MUDLARKS AND THE SILENT HIGHWAYMAN

SEGMENT 14

Albert got to his feet. “Perhaps I do have someone waiting, but I haven’t any chink.”

Albert got to his feet. “Perhaps I do have someone waiting, but I haven’t any chink.”

“A coin of any sort will do,” Alice said, “even a farthing.”

Albert searched. His hip pockets held nothing but gullyfluff.

Frustrated, he looked past Alice, saw George Hardly about twenty yards away. He’d come up quietly, possibly listening.

“Perhaps the ferryman is here for him,” Albert said. His heart sank at the thought.

Alice turned to look at Hardly. “Oh, yes, I’d forgot,” she said. “He awaits payment. Do you have coin, boy?”

Hardly approached cautiously. “No,” he said. “To cross the river?”

“Yes,” Albert said.

“They put pennies on my grandfather’s eyes, someone said to pay…” the older boy began, fear growing in his eyes. “Are we…? Did I…?”

No, Albert thought, don’t say the words. I cannot face it if I hear the words.

Thankfully, Hardly didn’t finish. He shook as if he might shed his troubling thoughts.

“There must be something,” Alice said. “He would not have come. I were with a girl when she found a memory of a coin. She let me touch it. The coin was the first earned by a man who became rich, a memory of how he’d built his fortune from humble beginnings. I believe he dropped it on the foreshore as he boarded the ferry. The ferryman came for the girl after she found it.”

“Sir,” Hardly said, turning to the one in the boat. “Would you take me to Limehouse? I’ve suffered grievous harm, and must get home.”

The stoney figure remained stock-still, his hand held out.

Albert turned back to Alice.“Mere remembrance brought forth coin?”

“Yes,” she said. “The rich man’s coin were like the soldier’s ship, a memory.”

The mudlark in Albert still sorted between things that should be taken up because they had worth and those to be ignored as worthless. He had been taught that fancies, hopes, and dreams had less value than what might be found in sooth. Yet, considering all that had happened that day, the boundary between actual experience and what occurred within his mind’s eye had become mirky. He wasn’t at all certain he’d awakened from his dream of the night before.

In that dream he’d found gold sovereigns at the wreck of the wherry. He’d placed the coins in the hidden pocket of his breeches.

“Gold has no worth but what the fancy of men give it,” his father had once said.

Against all reason, Albert ran his hand along the waistband of his breeches, trying to make it look like he merely pulled them up in case he was wrong.

He felt cold metal disks through the fabric.

How? I didn’t wear my breeches to bed! The foolishness of the thought nearly brought on a laugh, but he held it back.

Three coins, more than I need to pay the ferryman.

He might give one to Alice. She was deserving. But Hardly?

Albert considered the lesson he’d learned from dealing with Turvey, the one about hardening his heart.

If Hardly sees the gold, will he try to rob me? I could board the boat, leave them both behind. I might need the chink where I’m going.

Albert withdrew the coins, keeping them palmed and hidden. He looked warily at the older boy.

A scared child, George Hardly stood with a forlorn look, holding the hole in his chest with his right hand. He wasn’t frightening anymore.

No, a hard heart will get me nothing but the same from others.

Albert stepped up to him and held out a gold sovereign.

Hardly’s scarred features twisted grotesquely, but not toward the cruelty they had so often displayed. His brows bunched upward, and his chin quaked. A tear slid from his left eye, as he said, “Thank you.”

Albert offered Alice a coin. looking at the gold in his hand, glinting warmly in the gloom, she stood taller. Color returned to her face. Alice’s delighted features became youthful.

“He did not come for you alone!” she said with a giggle.

Boarding the boat, she dropped a dented oil can Albert had not seen in her possession. She seemed unaware that she’d done so. Similarly, Hardly left behind a blood-stained leather strap.

Stepping into the boat, and paying his fare, Albert wondered briefly what he might have dropped. He didn’t turn to look back.

Mere recollection of dream-stuff from the hope of his greatest find—the clinker-built wherry washed up on the foreshore of the Isle of Dogs—the gold had the worth Albert’s fancy gave it, enough to pay the fare for all three.

End

The full Mudlarks book itself, illustrated throughout by Alan, is available now on Amazon, and directly from the publisher through the links below:

mudlark ebook – ifd publishing

mudlark ebook – ifd publishing

mudlark paperback – ifd publishing

Author/Illustrator’s Note

I have been immersed in the history of Victorian London for nearly a decade while writing the Jack the Ripper Victims Series, novels about the lives of those killed by the Whitechapel Murderer. In the midst of research for the stories, I discovered all sorts of occupations of the period that involved scavenging and recycling. While that sounds good in the world of today that suffers such destruction from our various wastes, the recycling in Victorian times took a terrible toll on the health of those who did the work. During the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century, jobs were scarce and many achingly poor Londoners became willing to do the worst things in order to earn a crust. Toshers scavenged in the sewers. Bone grubbers collected bones door to door or by going through the rubbish of taverns or households that could afford to serve joints of beef, pork, or mutton. Purefinders collected feces in the streets. Night soil men emptied the human waste from cesspits and privy vaults. This one actually paid well, but because of that, many allowed their vaults and cesspits to overflow before they were willing to pay the price. Mudlarks, mostly children, scavenged the banks of the River Thames, looking for anything that had been lost in the water and might be found at low tide in the exposed area known as the foreshore. Markets existed for nearly all that was collected, yet the returns were paltry considering the time and energy involved and the risks to health.

A time when the majority of transportation employed horses, the streets were littered with dung and awash in over ten thousand gallons of equine urine each day. That and the leakage from overflowing cesspits and privy vaults found its way into the River Thames when the rains came. As a result, the river reeked.

The people of London recognized that much illness came from the river. The common belief was that illness was born on bad smells—miasma as it was called—and that people became ill when breathing the malodorous air. The city was in fact suffering outbreaks of deadly waterborne illness during a time when much of the science of microbes was still under debate.

I write this during the COVID-19 flu pandemic, and while knowing something of the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic that infected approximately 500 million people. In comparison, the waterborne epidemics of Victorian London were small events, except to those who suffered through them.

In the back of this volume, the reader will find a short article about the dangers of illness from the Thames in Victorian times, and The Great Stink, a nearly two-month-long period in the summer of 1858, during which those who could afford to do so, evacuated London to get away from the smell coming off the river.

In such periods of fouled water and air, the poor, needing the income, or fearing unemployment, continued to work, despite the dangers of disease, real or perceived.

This is a fanciful story about a mudlark and the choices he made within that environment.

—Alan M. Clark

Eugene, Oregon

So many thanks!!!